Discrete performance distributions

When we collect software performance measurements, we get a bunch of time intervals. Typically, we tend to interpret time values as continuous values. However, the obtained values are actually discrete due to the limited resolution of our measurement tool. In simple cases, we can treat these discrete values as continuous and get meaningful results. Unfortunately, discretization may produce strange phenomena like pseudo-multimodality or zero dispersion. If we want to set up a reliable system that automatically analyzes such distributions, we should be aware of such problems so we could correctly handle them.

In this post, I want to share a few of discretization problems in real-life performance data sets (based on the Rider performance tests).

General discretization

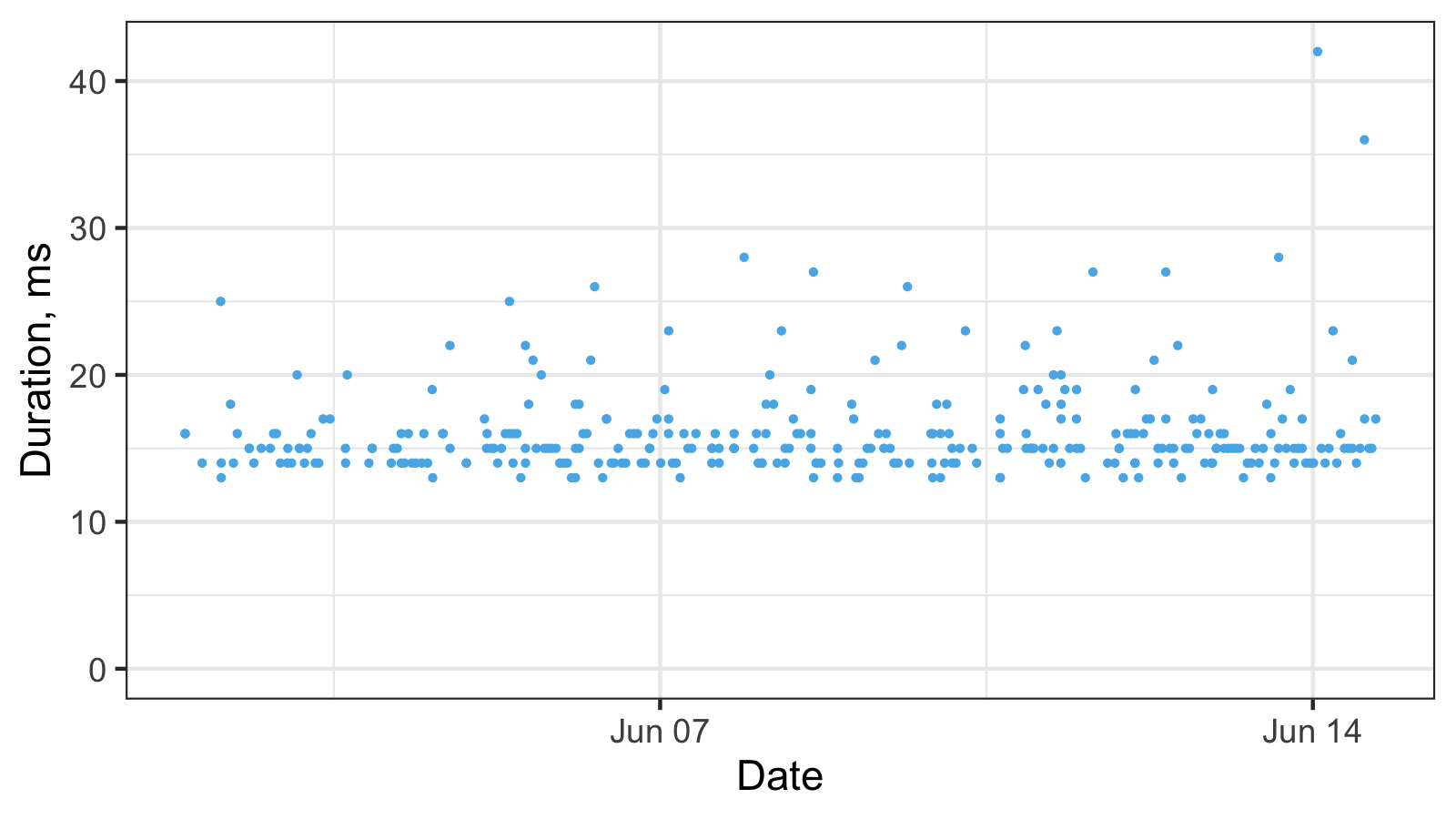

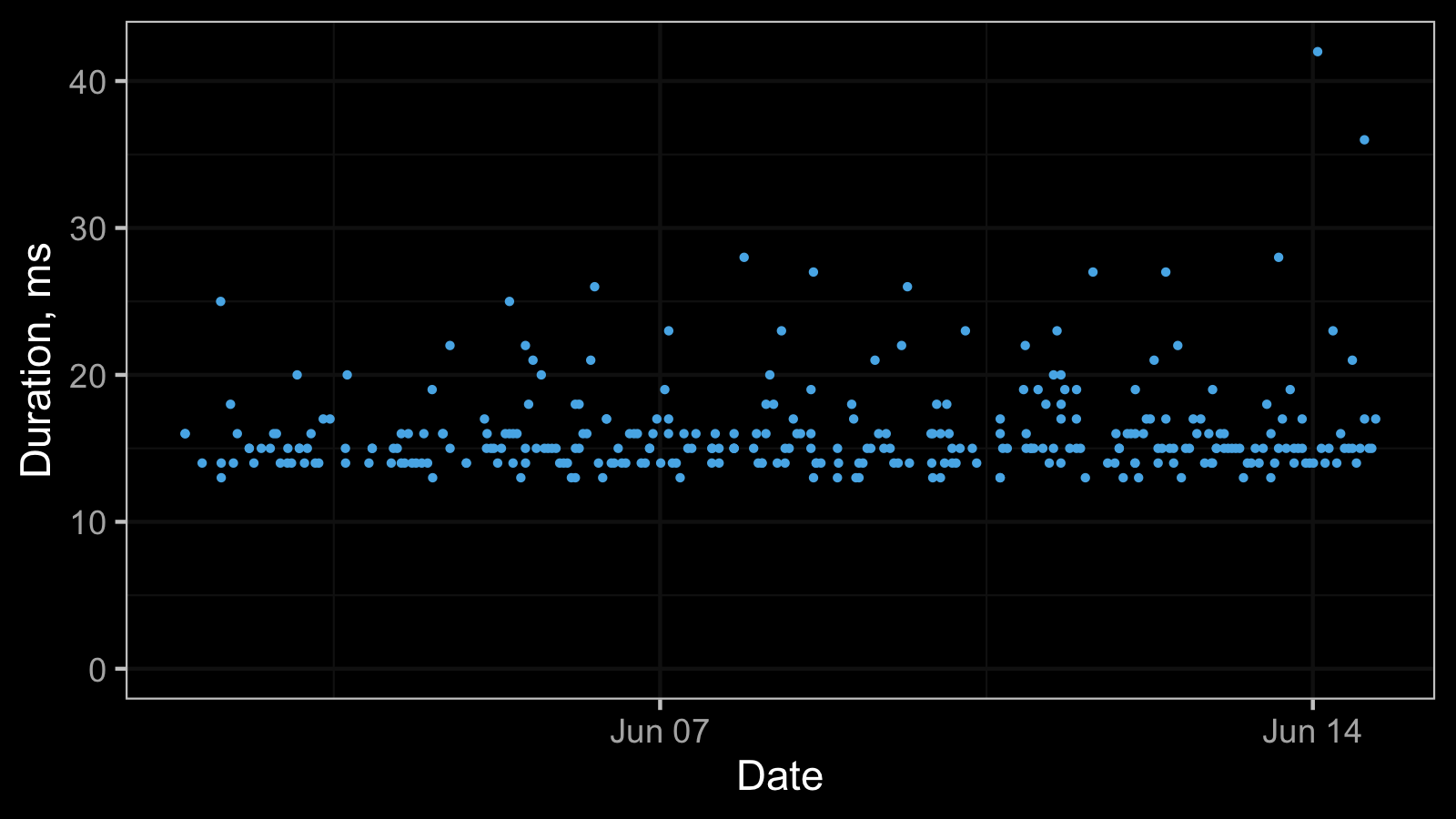

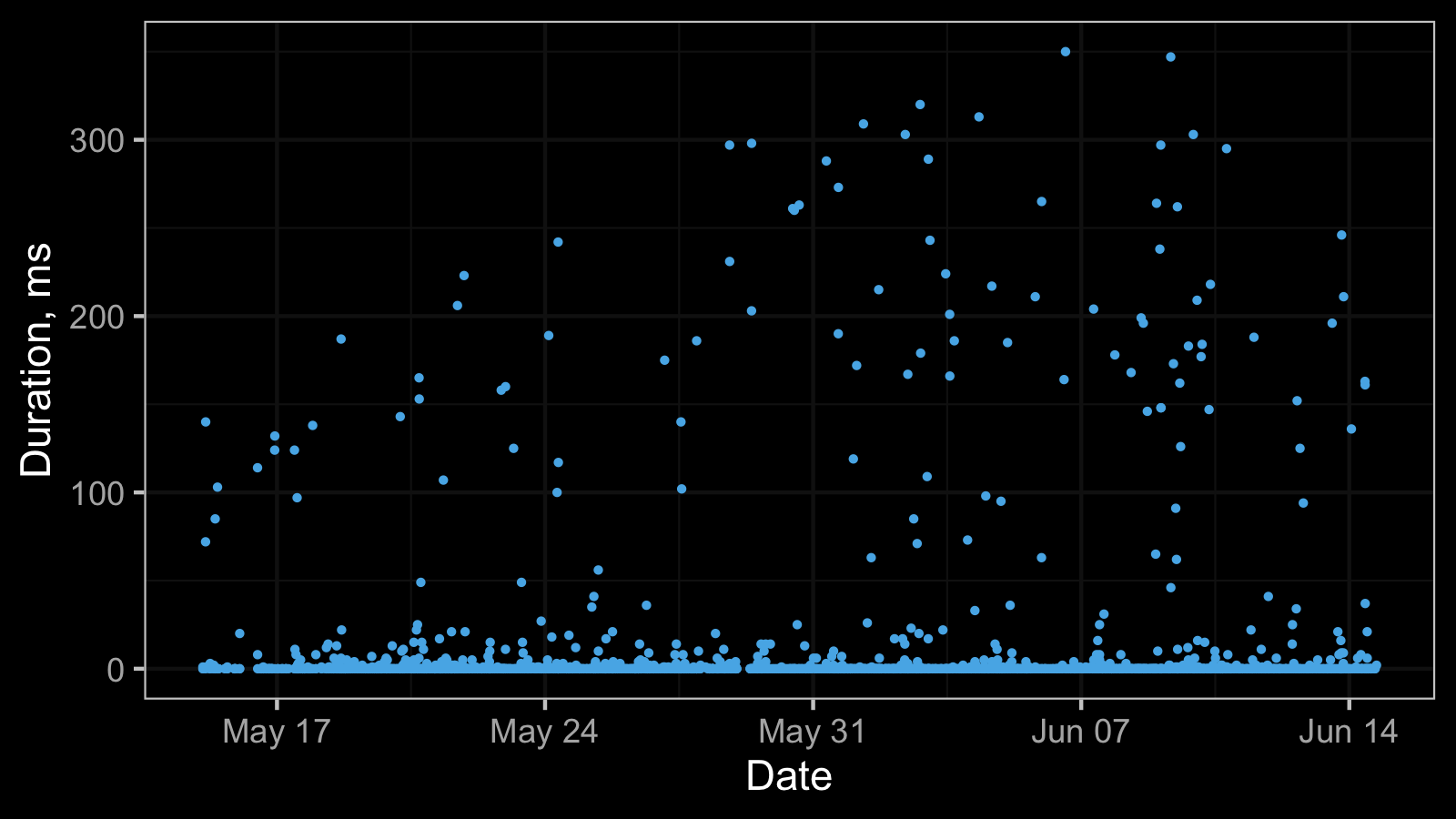

The most simple way to get discretization phenomena is to limit the resolution of your performance measurements to milliseconds. It’s a perfectly legitimate approach when you don’t care about better precision. As a result, we can obtain a timeline plot like this:

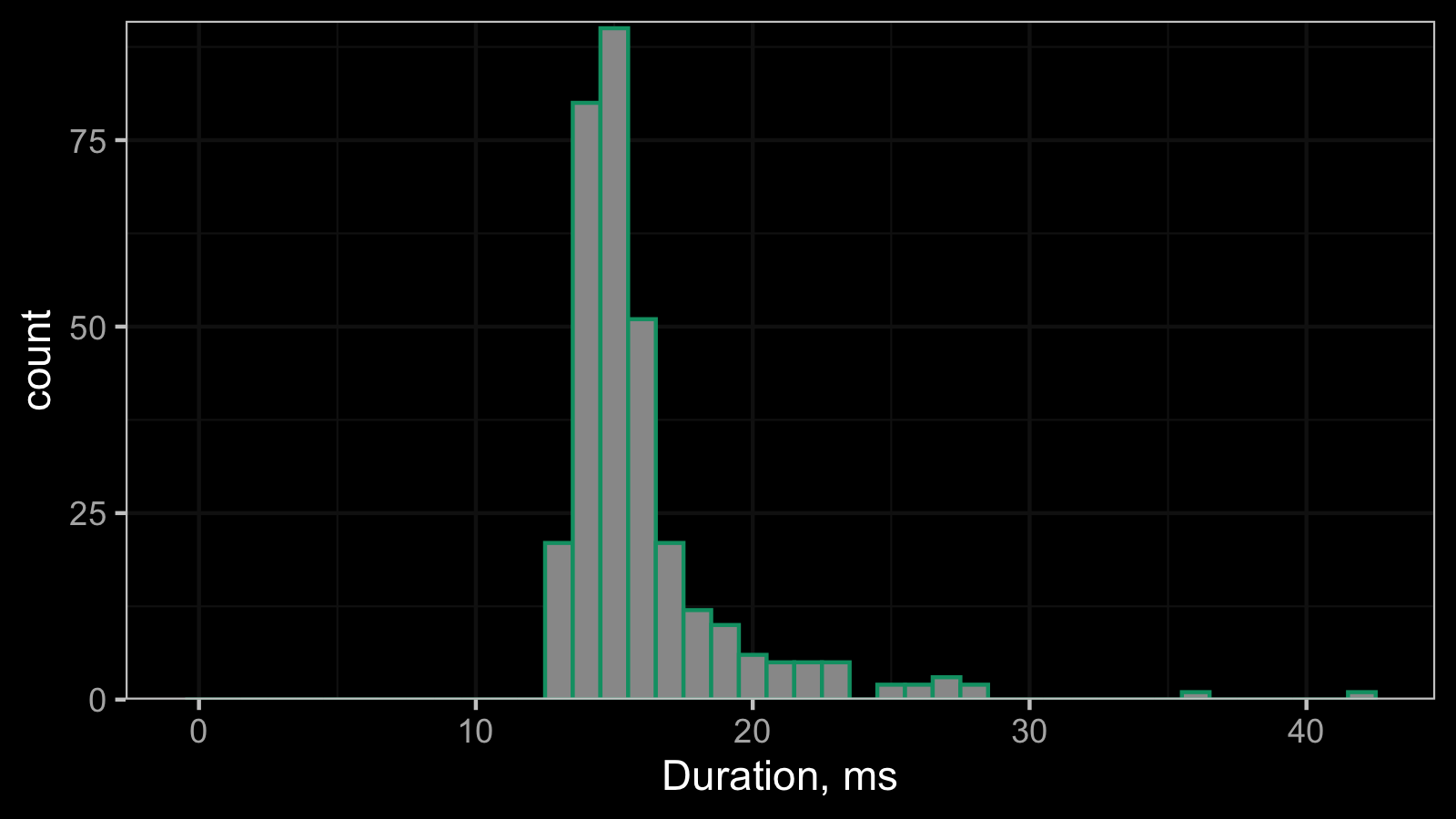

And here is the corresponding histogram (binwidth = 1):

This histogram can be treated as an estimation of the probability mass function of the underlying discrete distribution. However, if we try to treat this distribution as a continuous one and build a density estimation, we can get a corrupted visualization. This problem can be resolved for different kinds of density estimations using jittering (I already blogged about how to do it for the kernel density estimation (KDE) and quantile-respectful density estimation (QRDE)).

Zero median and zero MAD

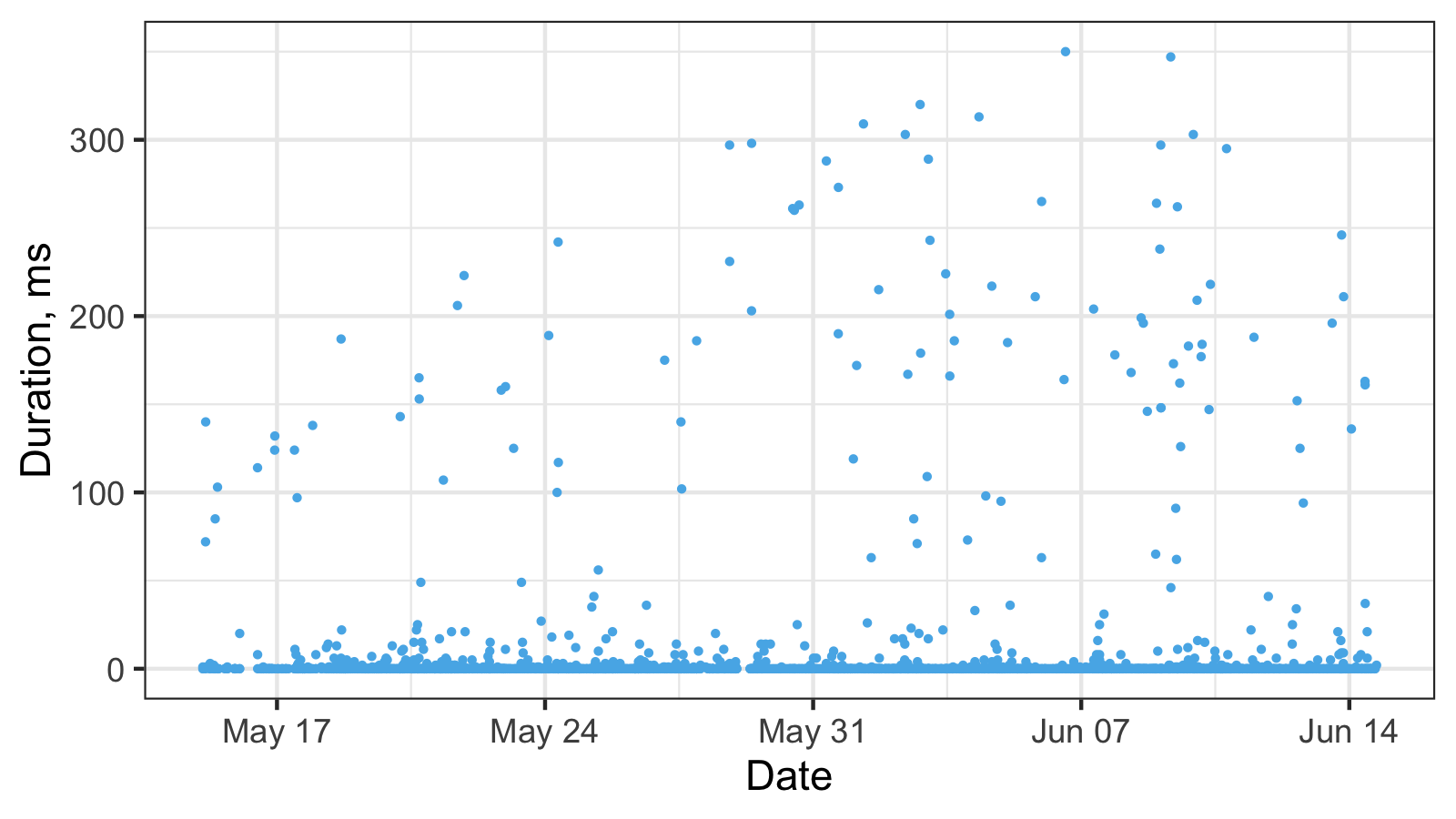

Here is another timeline plot based on real-life performance measurements:

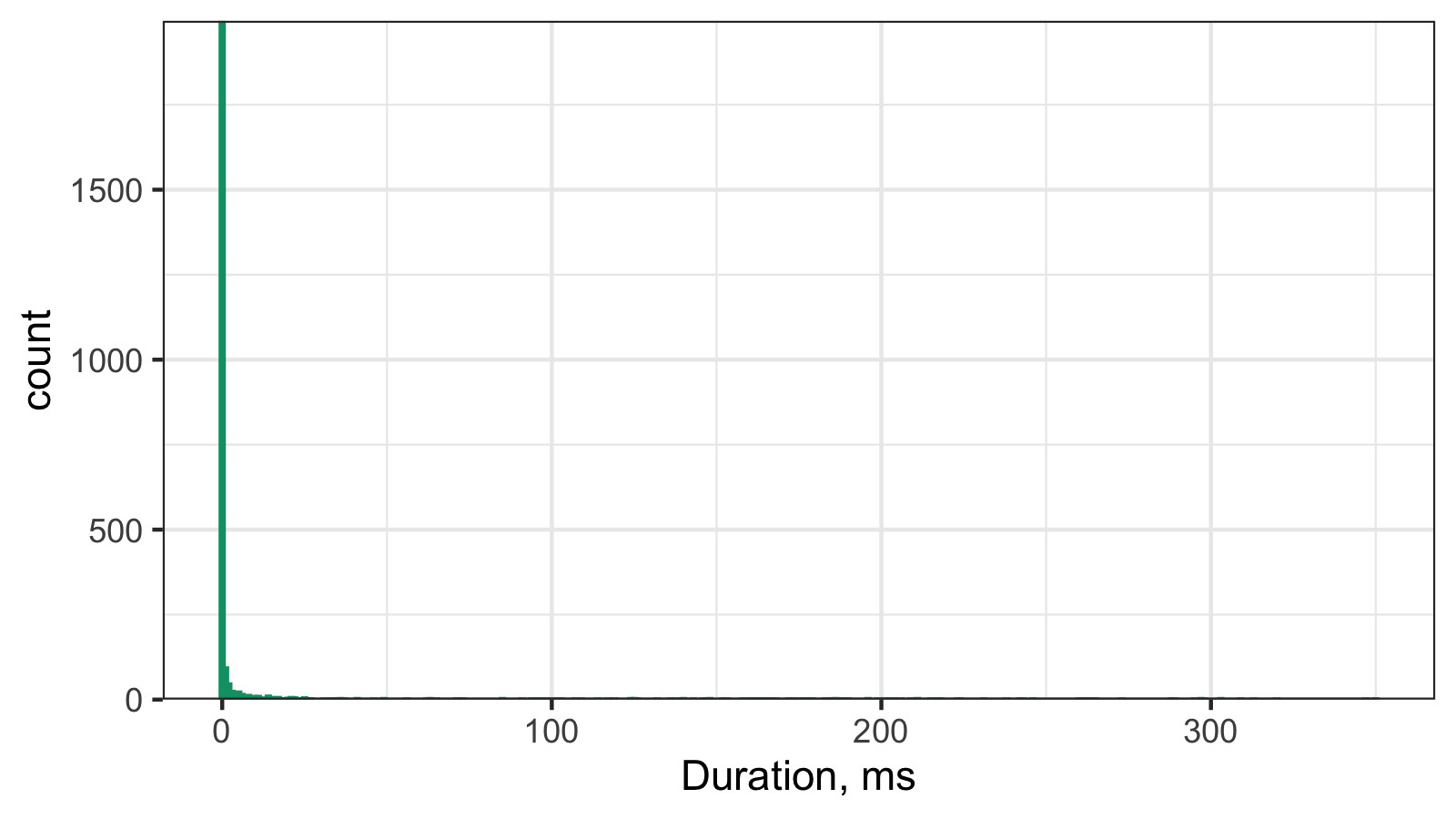

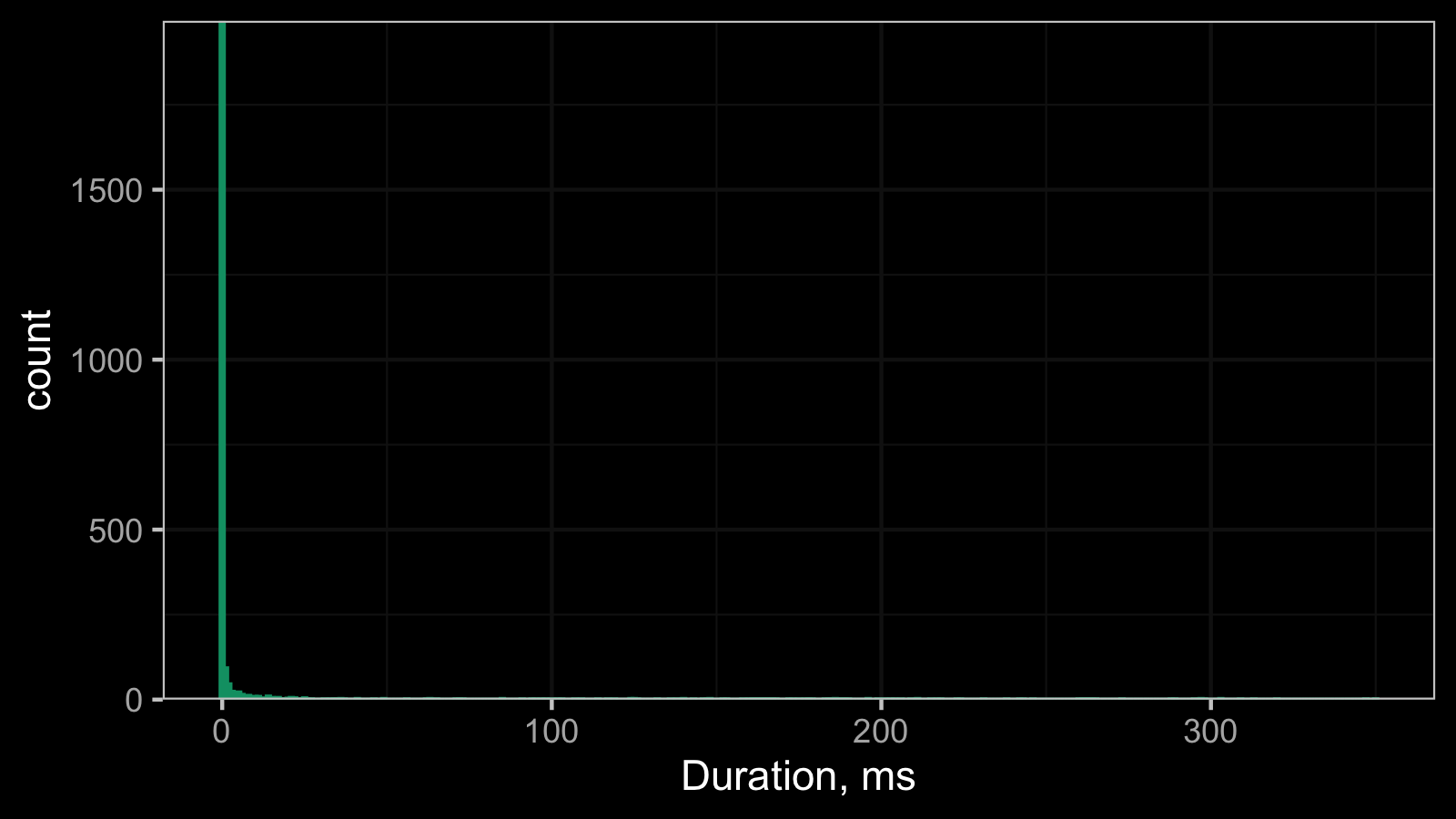

And here is the corresponding histogram:

It’s hard to work with such a histogram because of the scale, so here is its raw data:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

1996 92 45 23 20 21 14 5 11 5 8 8 3 3 9 5

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 26 27 31 33 34 35 36

3 5 1 1 3 5 4 1 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 2

37 41 46 49 56 62 63 65 71 72 73 85 91 94 95 97

1 2 1 2 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1

98 100 102 103 107 109 114 117 119 124 125 126 132 136 138 140

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 2

143 146 147 148 152 153 158 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168

1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

172 173 175 177 178 179 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 196 199

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 2 1

201 203 204 206 209 211 215 217 218 223 224 231 238 242 243 246

1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

260 261 262 263 264 265 273 288 289 295 297 298 303 309 313 320

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 2 1 1 1

347 350

1 1

These numbers mean the follow: we observed 0ms 1996 times, 1ms 92 times, 2ms 45 times, and so on.

And here are the same set of numbers scaled to percents:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

82.68 3.81 1.86 0.95 0.83 0.87 0.58 0.21 0.46 0.21 0.33 0.33 0.12

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 26

0.12 0.37 0.21 0.12 0.21 0.04 0.04 0.12 0.21 0.17 0.04 0.17 0.04

27 31 33 34 35 36 37 41 46 49 56 62 63

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.08

65 71 72 73 85 91 94 95 97 98 100 102 103

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04

107 109 114 117 119 124 125 126 132 136 138 140 143

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04

146 147 148 152 153 158 160 161 162 163 164 165 166

0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04

167 168 172 173 175 177 178 179 183 184 185 186 187

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04

188 189 190 196 199 201 203 204 206 209 211 215 217

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04

218 223 224 231 238 242 243 246 260 261 262 263 264

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04

265 273 288 289 295 297 298 303 309 313 320 347 350

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04

Thus, we observed 0ms in the 92.69% cases, 1ms in the 3.81% cases, 2ms in 1.86% cases, and so on.

In this data set, both the median and the median absolute deviations are zero.

It produces some complications if you use the median as the primary summary metric.

There are two main ways to resolve this problem. The first one is to work with higher quantiles instead of the median. In this case, we can describe the dispersion using the quantile absolute deviation (QAD) instead of the median absolute deviation (MAD). The second way is to build a model that describes the underlying distribution. In the above example, the observed data could be perfectly described using the discrete Weibull distribution. However, this approach is much more complicated in the general case and it requires decent skills in the extreme value theory.

Dirac delta function

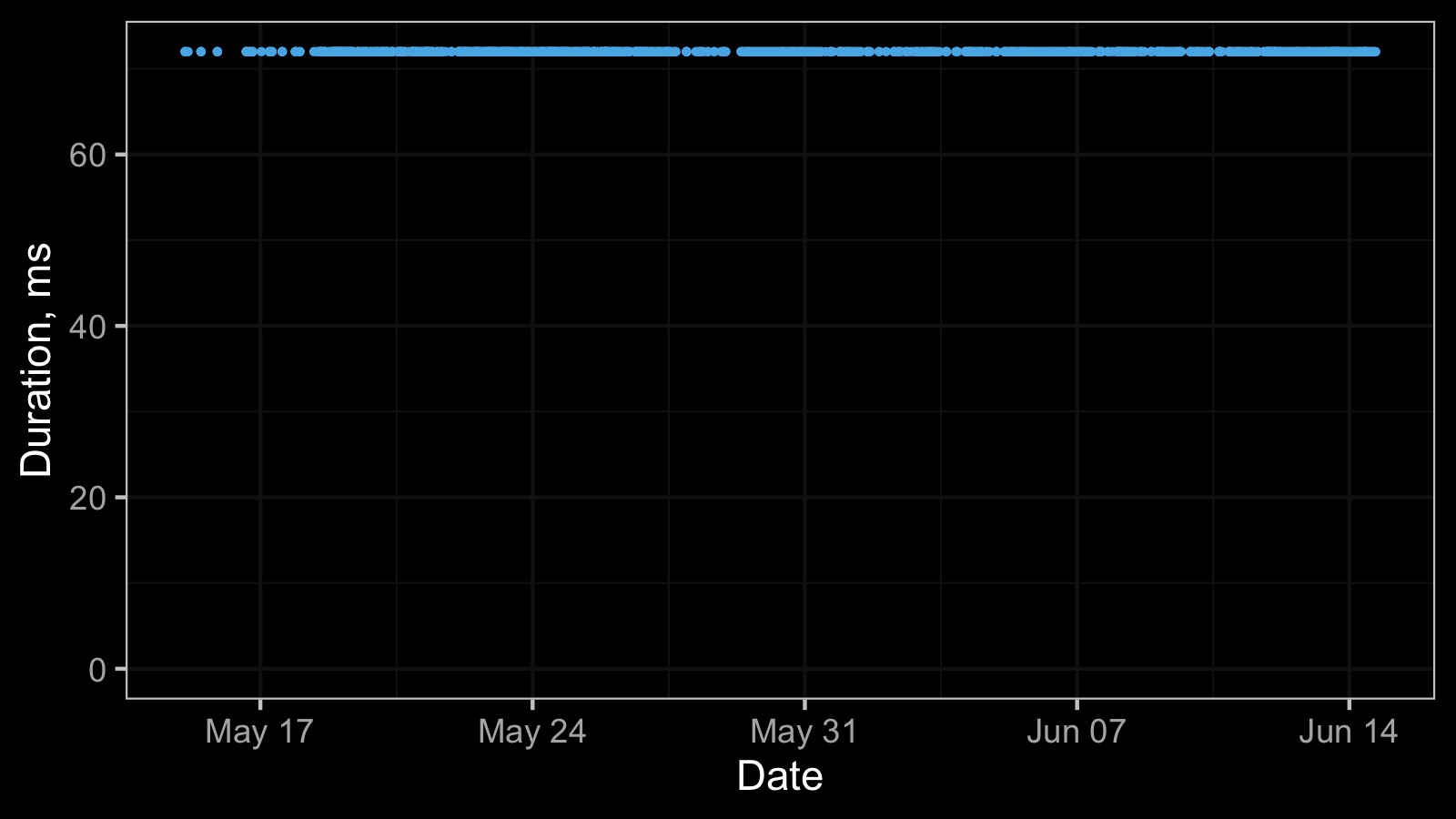

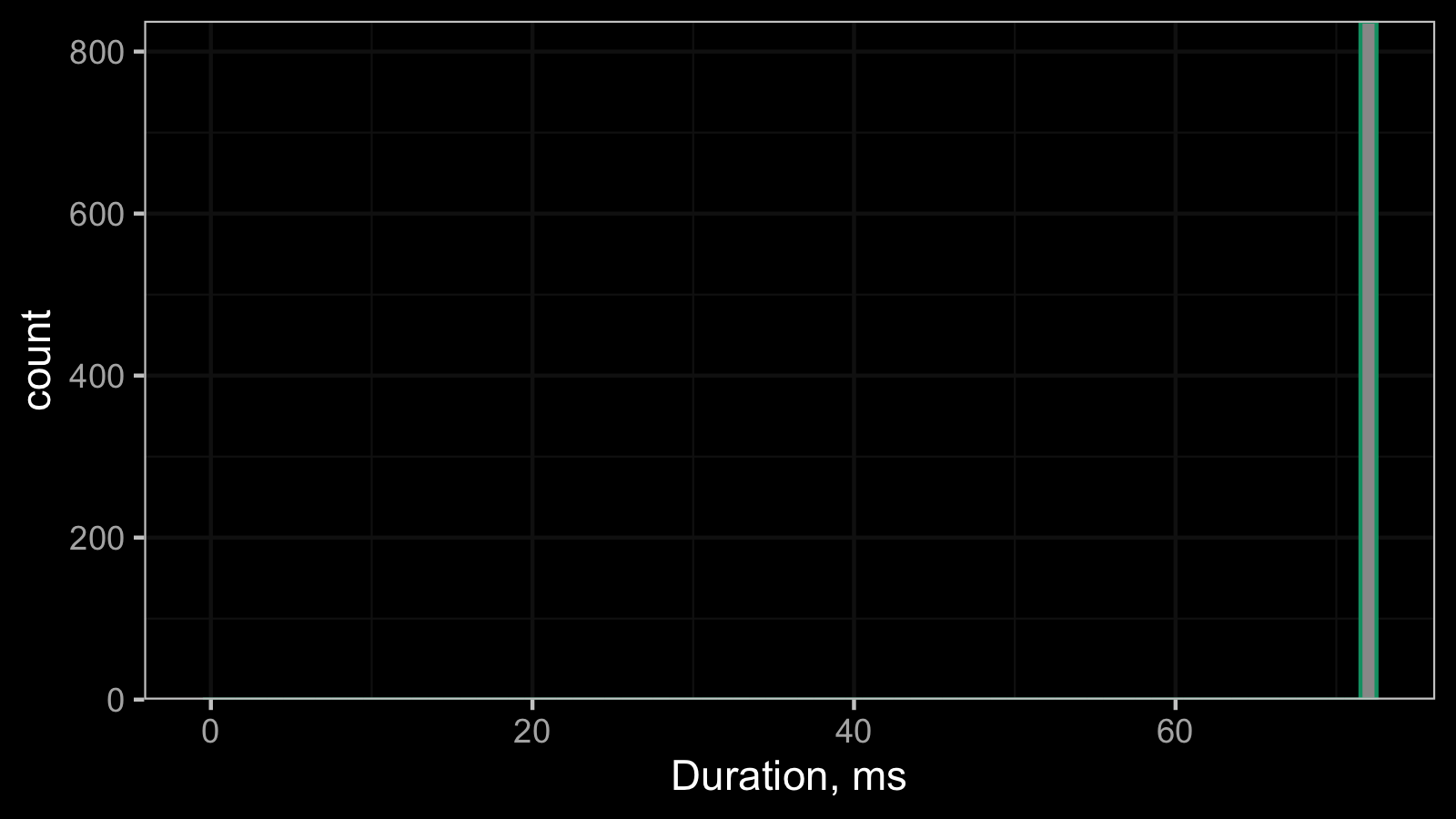

And here is one more timeline plot:

All the observed values are equal, so the corresponding histogram contains a single bin:

This constant distribution can be described using the Dirac delta function. Non-zero constant distribution is not so typical for time measurements, but it’s a common pattern for advanced performance metrics like the number of garbage collections or the final memory footprint.

Conclusion

The real-life samples are not always easy to analyze. There is always a risk of getting a “corner case” distribution (e.g., with zero dispersion) that will completely break your “general case” equations. If you want to set up an automatic system that works with real-life data, it’s always a good idea to think about such cases in advance and implement corresponding checks.