Standard quantile absolute deviation

The below text contains an intermediate snapshot of the research and is preserved for historical purposes.

The median absolute deviation (MAD) is a popular robust replacement of the standard deviation (StdDev). It’s truly robust: its breakdown point is $50\%$. However, it’s not so efficient when we use it as a consistent estimator for the standard deviation under normality: the asymptotic relative efficiency against StdDev (we call it the Gaussian efficiency) is only about $\approx 37\%$.

In practice, such robustness is not always essential, while we typically want to have the highest possible efficiency. I already described the concept of the quantile absolute deviation which aims to provide a customizable trade-off between robustness and efficiency. In this post, I would like to suggest a new default option for this measure of dispersion called the standard quantile absolute deviation. Its Gaussian efficiency is $\approx 54\%$ while the breakdown point is $\approx 32\%$

Introduction

In the context of this post, we consider the quantile absolute deviation ($\operatorname{QAD}$) around the median:

$$ \newcommand{MAD}{\operatorname{MAD}} \newcommand{QAD}{\operatorname{QAD}} \newcommand{SQAD}{\operatorname{SQAD}} \newcommand{Q}{\operatorname{Q}} \newcommand{SD}{\operatorname{SD}} \newcommand{QHF}{\operatorname{Q}_{\operatorname{HF7}}} \newcommand{QHD}{\operatorname{Q}_{\operatorname{HD}}} \newcommand{QTHD}{\operatorname{Q}_{\operatorname{THD-SQRT}}} \newcommand{erf}{\operatorname{erf}} \newcommand{erfinv}{\operatorname{erf}^{-1}} \newcommand{E}{\mathbb{E}} \newcommand{V}{\mathbb{V}} \QAD(X, p) = \Q(|X - \Q(X, 0.5)|, p), $$where $Q$ is a quantile estimator, X is a sample of i.i.d. random variables $X = \{ X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n \}$.

Obviously, the median absolute deviation is a special case of $\operatorname{QAD}$:

$$ \MAD(X) = \Q(|X - \Q(X, 0.5)|, 0.5) = \QAD(X, 0.5). $$As for $\Q$, we consider the traditional quantile estimator $\QHF$

(Type 7 in the Hyndman-Fan taxonomy, see Sample Quantiles in Statistical Packages

By Rob J Hyndman, Yanan Fan

·

1996hyndman1996).

Efficiency vs. robustness

The classic standard equation estimator provides great Gaussian efficiency for the standard deviation, but it is not robust (the breakdown point is 0.0). The median absolute deviation provides poor Gaussian efficiency, but it is highly robust (the breakdown point is 0.5). When we choose an estimator, we always have to deal with a trade-off between efficiency and robustness. Finding the right balance can be a challenging task.

It is said that $\MAD$ has the highest possible breakdown point for a scale estimator. Though, we have a theoretical option to build a scale estimator with a higher breakdown point (e.g., $\QAD(X, 0.25)$). However, such an estimator would not make much sense. Indeed, if more than 50% of the sample elements are corrupted by outliers, these outliers become the major part of the distribution. If these outliers are non-representative (obtained due to measurements error or other technical mistakes; gross errors), we should completely ignore them or reconsider the way we collect the data. Moreover, if the median itself is corrupted, estimating the deviation around the median is meaningless. If these outliers are representative (actually describe the true nature of the underlying model), we should treat them as a part of the distribution.

While 0.5 is the highest breakdown point for a scale estimator, it is not necessarily the optimal one. Let us consider a situation when 49% of a sample is contaminated by outliers. The $\MAD$ could handle such a situation and provide a non-corrupted estimation. But do we really want to use $\MAD$ in such a situation? If 49% of sample elements are outliers, do we really want to consider them as outliers? At some moment, it makes sense to consider them as an essential part of a distribution. Probably the distribution is multimodal, and it makes sense to consider each mode separately. Anyway, a single $\MAD$ value can be quite misleading in such a situation.

Now let us say that we have learned to detect samples with a significant number of outliers to analyze them using a dedicated approach. In this case, we do not really need the 0.5 breakdown point. This means that we can trade some robustness for statistical efficiency. The next reasonable question is how to choose the optimal breakdown point.

Choosing the breakdown point

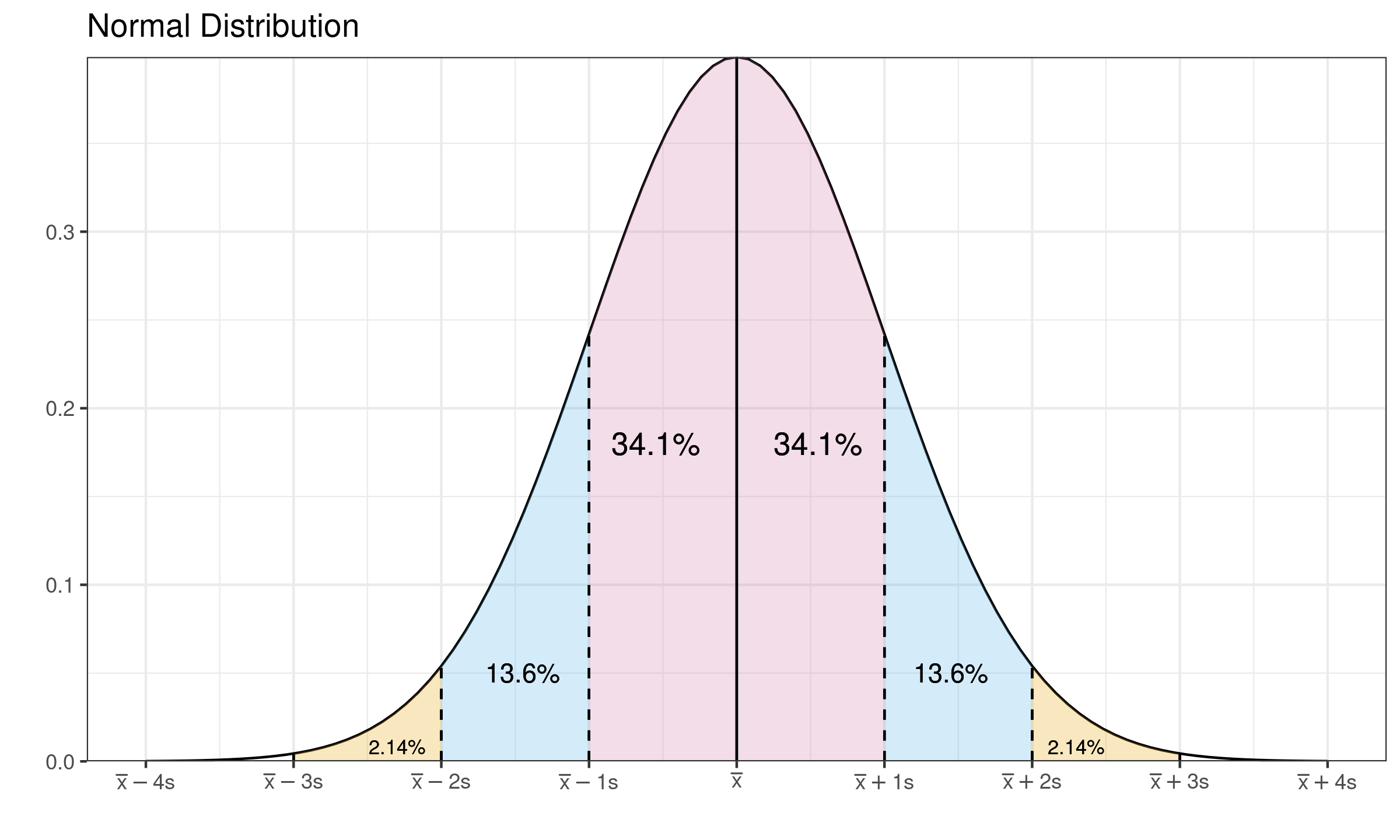

Let us recall the density plot of the normal distribution:

The $\MAD$ and other measures of dispersion are often used as consistency estimators for the standard deviation. The idea is simple: we estimate the $\MAD$, multiply it by a scale constant and get the standard deviation. It works well when the distribution is continuous, light-tailed, unimodal, and with only slight deviations from normality. In this case, we typically assume that the interval $[\mu-\sigma; \mu+\sigma]$ is not so distorted compared to the normal distribution. This assumption is violated if some elements of $[\mu-\sigma; \mu+\sigma]$ are corrupted. Let us consider the “protection” of this interval as a reference condition for choosing the breakdown point. For the normal distribution, $[\mu-\sigma; \mu+\sigma]$ covers exactly $\Phi(1)-\Phi(-1) = 2\Phi(1) - 1 \approx 0.6827 = 68.27\%$ of the distribution. It gives us a breakdown point which is equal to $1 - (\Phi(1)-\Phi(-1)) \approx 0.3173 = 31.73\%$. It could be interpreted as follows: if less than one-third of the distribution is contaminated, we are in the safe zone: the scale estimations are not corrupted. If more than one-third of the distribution is contaminated, we should split the distribution into several modes and analyze each mode independently. The breakdown point of $37.73\%$ looks like an admissible value.

The standard quantile absolute deviation

Since we have the desired asymptotic breakdown point, we can define the corresponding measure of scale using $\QAD$. Let us denote it by the standard quantile absolute deviation or $\SQAD$. Asymptotically, it can be defined as follows:

$$ \SQAD(X) = \QAD(X, 2\Phi(1) - 1). $$There is no need to introduce a scale constant:

the asymptotic expected value of $\SQAD$ for the normal distribution is 1

(since the sample quantile are Fisher-consistent for the distribution quantiles when $f(p)>0$ (see Theorem 8.5.1 in A first course in order statistics

By Barry C Arnold, N Balakrishnan, H N Nagaraja

·

2008arnold2008),

$\SQAD$ is Fisher-consistent for the standard deviation):

If we want to make $\SQAD$ an unbiased estimator for $\SD$ under normality, we have to introduce the bias-correction factor $C_n$:

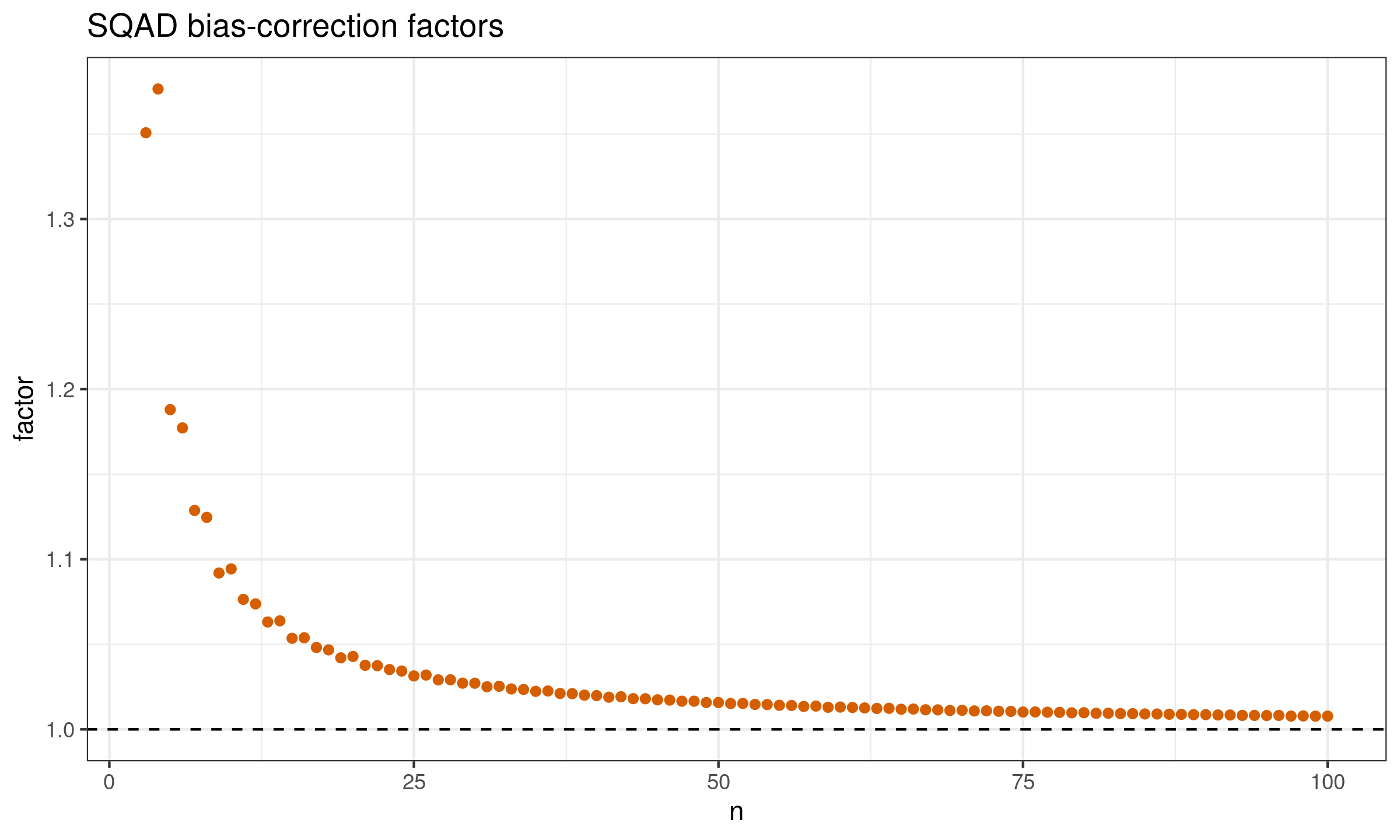

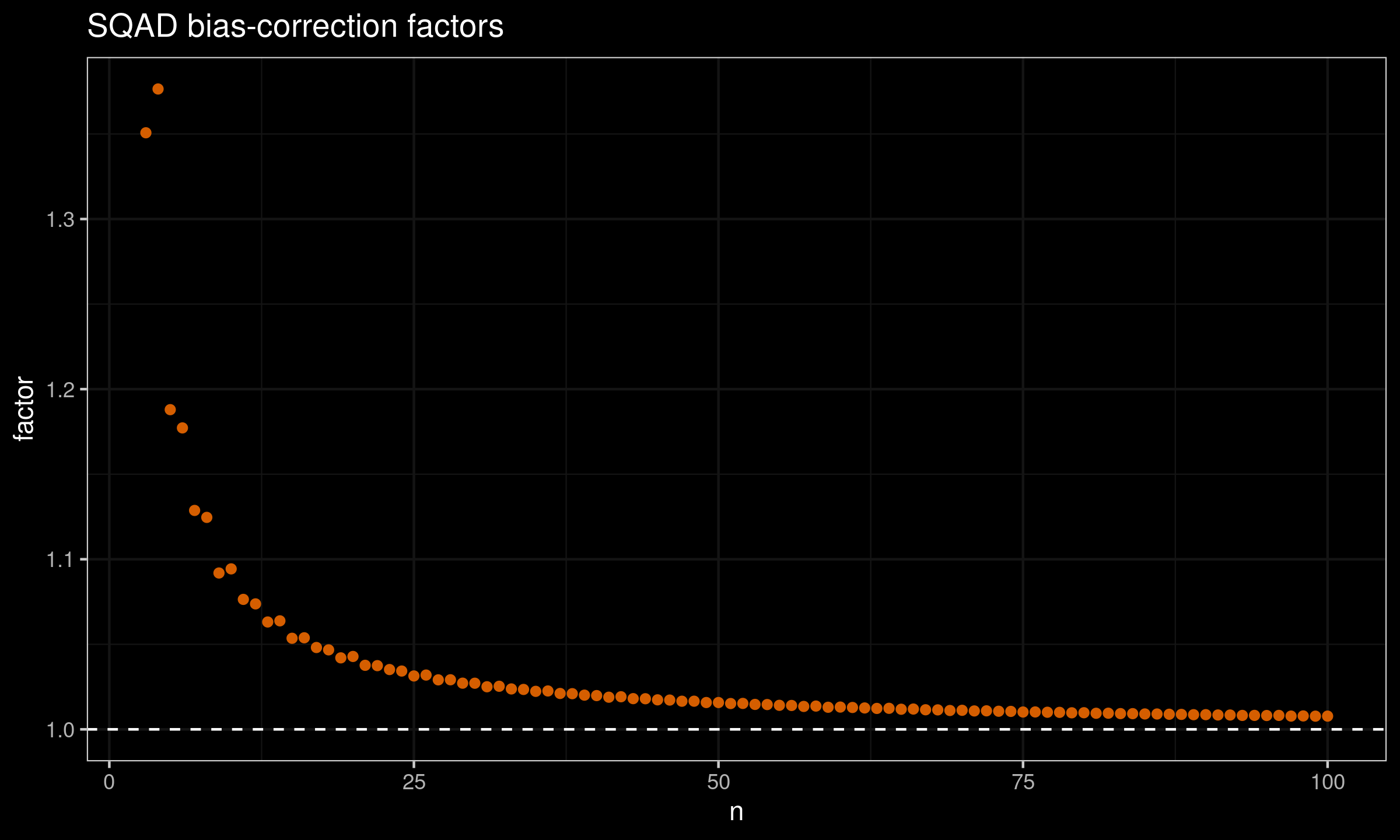

$$ \SQAD_n(X) = C_n \cdot \QAD(X, 2\Phi(1) - 1). $$The factor values can be easily obtained using Monte-Carlo simulations. Here is the plot with these values for $n \leq 100$:

And here are the raw factor values:

| n | factor |

|---|---|

| 3 | 1.35070 |

| 4 | 1.37644 |

| 5 | 1.18794 |

| 6 | 1.17720 |

| 7 | 1.12869 |

| 8 | 1.12460 |

| 9 | 1.09191 |

| 10 | 1.09434 |

| 11 | 1.07640 |

| 12 | 1.07376 |

| 13 | 1.06312 |

| 14 | 1.06379 |

| 15 | 1.05354 |

| 16 | 1.05383 |

| 17 | 1.04811 |

| 18 | 1.04673 |

| 19 | 1.04203 |

| 20 | 1.04285 |

| 21 | 1.03765 |

| 22 | 1.03745 |

| 23 | 1.03516 |

| 24 | 1.03428 |

| 25 | 1.03139 |

| 26 | 1.03192 |

| 27 | 1.02910 |

| 28 | 1.02915 |

| 29 | 1.02715 |

| 30 | 1.02712 |

| 31 | 1.02504 |

| 32 | 1.02533 |

| 33 | 1.02376 |

| 34 | 1.02346 |

| 35 | 1.02234 |

| 36 | 1.02257 |

| 37 | 1.02110 |

| 38 | 1.02097 |

| 39 | 1.02011 |

| 40 | 1.01985 |

| 41 | 1.01890 |

| 42 | 1.01917 |

| 43 | 1.01806 |

| 44 | 1.01800 |

| 45 | 1.01735 |

| 46 | 1.01722 |

| 47 | 1.01654 |

| 48 | 1.01655 |

| 49 | 1.01577 |

| 50 | 1.01577 |

| 51 | 1.01518 |

| 52 | 1.01524 |

| 53 | 1.01466 |

| 54 | 1.01458 |

| 55 | 1.01413 |

| 56 | 1.01404 |

| 57 | 1.01347 |

| 58 | 1.01369 |

| 59 | 1.01299 |

| 60 | 1.01310 |

| 61 | 1.01286 |

| 62 | 1.01258 |

| 63 | 1.01230 |

| 64 | 1.01237 |

| 65 | 1.01183 |

| 66 | 1.01194 |

| 67 | 1.01151 |

| 68 | 1.01145 |

| 69 | 1.01109 |

| 70 | 1.01120 |

| 71 | 1.01082 |

| 72 | 1.01089 |

| 73 | 1.01065 |

| 74 | 1.01056 |

| 75 | 1.01019 |

| 76 | 1.01023 |

| 77 | 1.01006 |

| 78 | 1.00999 |

| 79 | 1.00973 |

| 80 | 1.00977 |

| 81 | 1.00945 |

| 82 | 1.00949 |

| 83 | 1.00926 |

| 84 | 1.00923 |

| 85 | 1.00905 |

| 86 | 1.00903 |

| 87 | 1.00888 |

| 88 | 1.00879 |

| 89 | 1.00862 |

| 90 | 1.00864 |

| 91 | 1.00845 |

| 92 | 1.00843 |

| 93 | 1.00819 |

| 94 | 1.00821 |

| 95 | 1.00813 |

| 96 | 1.00820 |

| 97 | 1.00780 |

| 98 | 1.00789 |

| 99 | 1.00776 |

| 100 | 1.00778 |

| 109 | 1.00700 |

| 110 | 1.00698 |

| 119 | 1.00643 |

| 120 | 1.00642 |

| 129 | 1.00585 |

| 130 | 1.00597 |

| 139 | 1.00550 |

| 140 | 1.00557 |

| 149 | 1.00516 |

| 150 | 1.00514 |

| 159 | 1.00484 |

| 160 | 1.00479 |

| 169 | 1.00452 |

| 170 | 1.00460 |

| 179 | 1.00429 |

| 180 | 1.00426 |

| 189 | 1.00401 |

| 190 | 1.00406 |

| 199 | 1.00378 |

| 200 | 1.00381 |

| 249 | 1.00307 |

| 250 | 1.00307 |

| 299 | 1.00258 |

| 300 | 1.00259 |

| 349 | 1.00219 |

| 350 | 1.00219 |

| 399 | 1.00192 |

| 400 | 1.00190 |

| 449 | 1.00173 |

| 450 | 1.00168 |

| 499 | 1.00151 |

| 500 | 1.00152 |

| 600 | 1.00126 |

| 700 | 1.00109 |

| 800 | 1.00094 |

| 900 | 1.00086 |

| 1000 | 1.00076 |

| 1500 | 1.00050 |

| 2000 | 1.00038 |

| 3000 | 1.00026 |

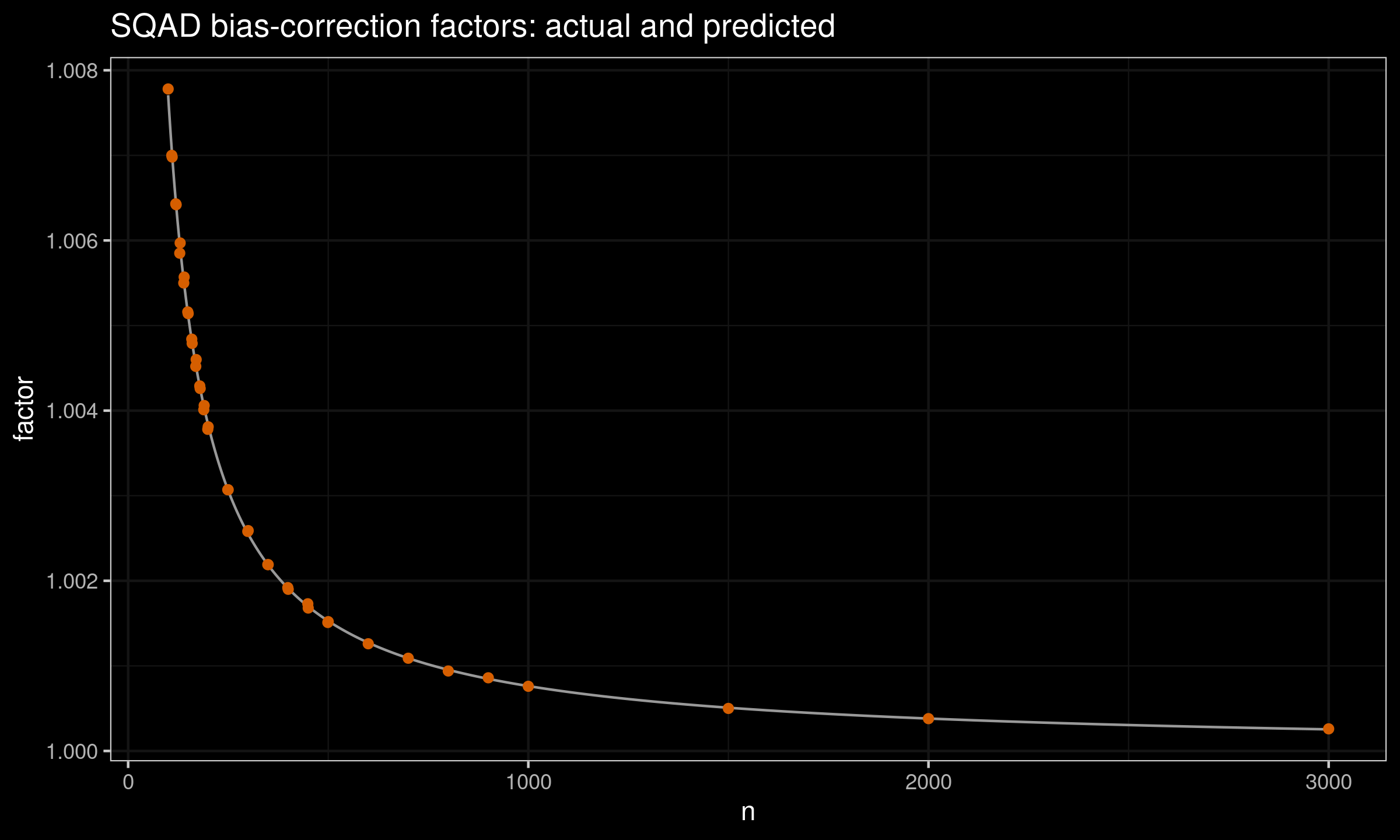

For $n>100$, we can use the following prediction equation (obtained using least squares):

$$ C_n = 1 + 0.762 n +0.868 n^2. $$This equation perfectly matches the existing estimations:

The statistical efficiency of SQAD and MAD

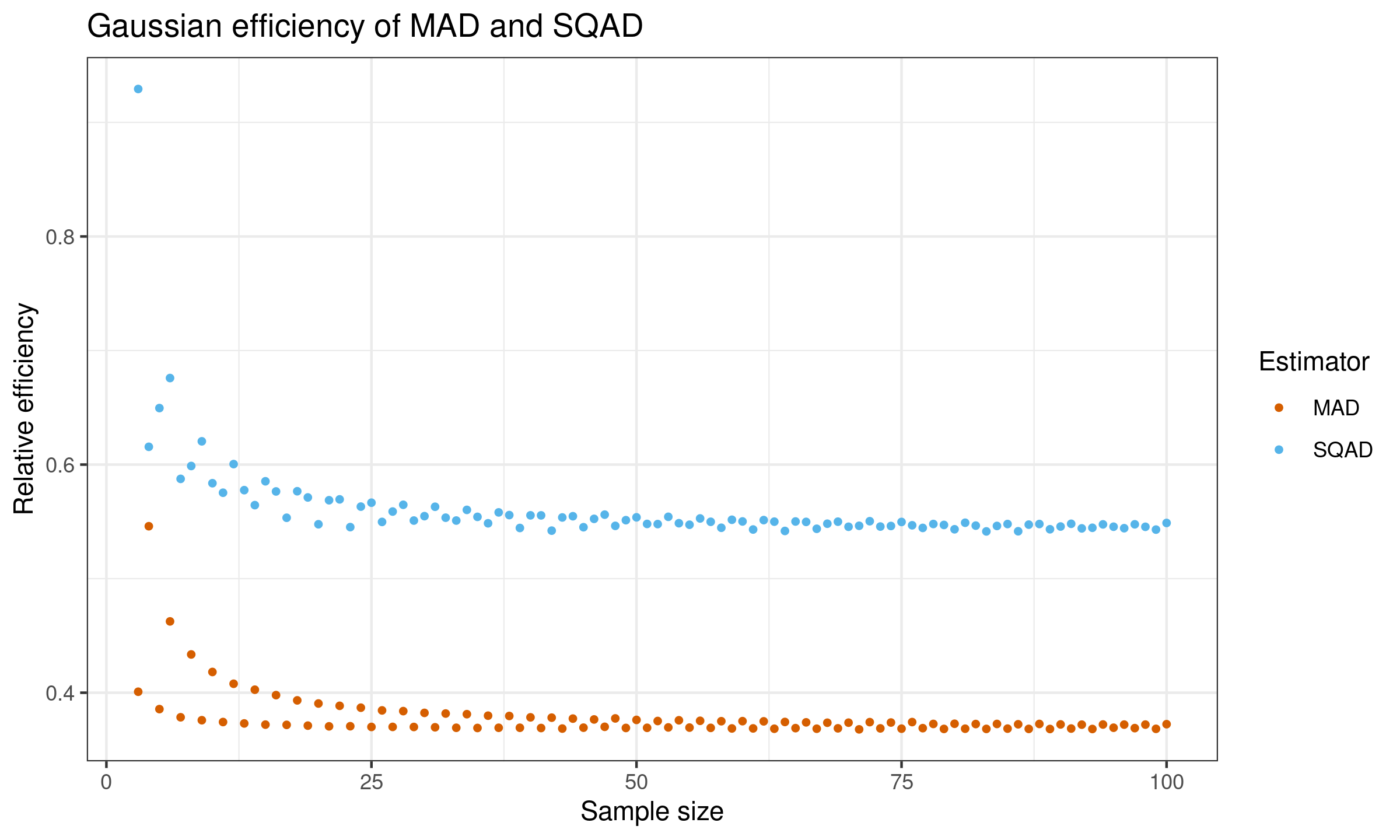

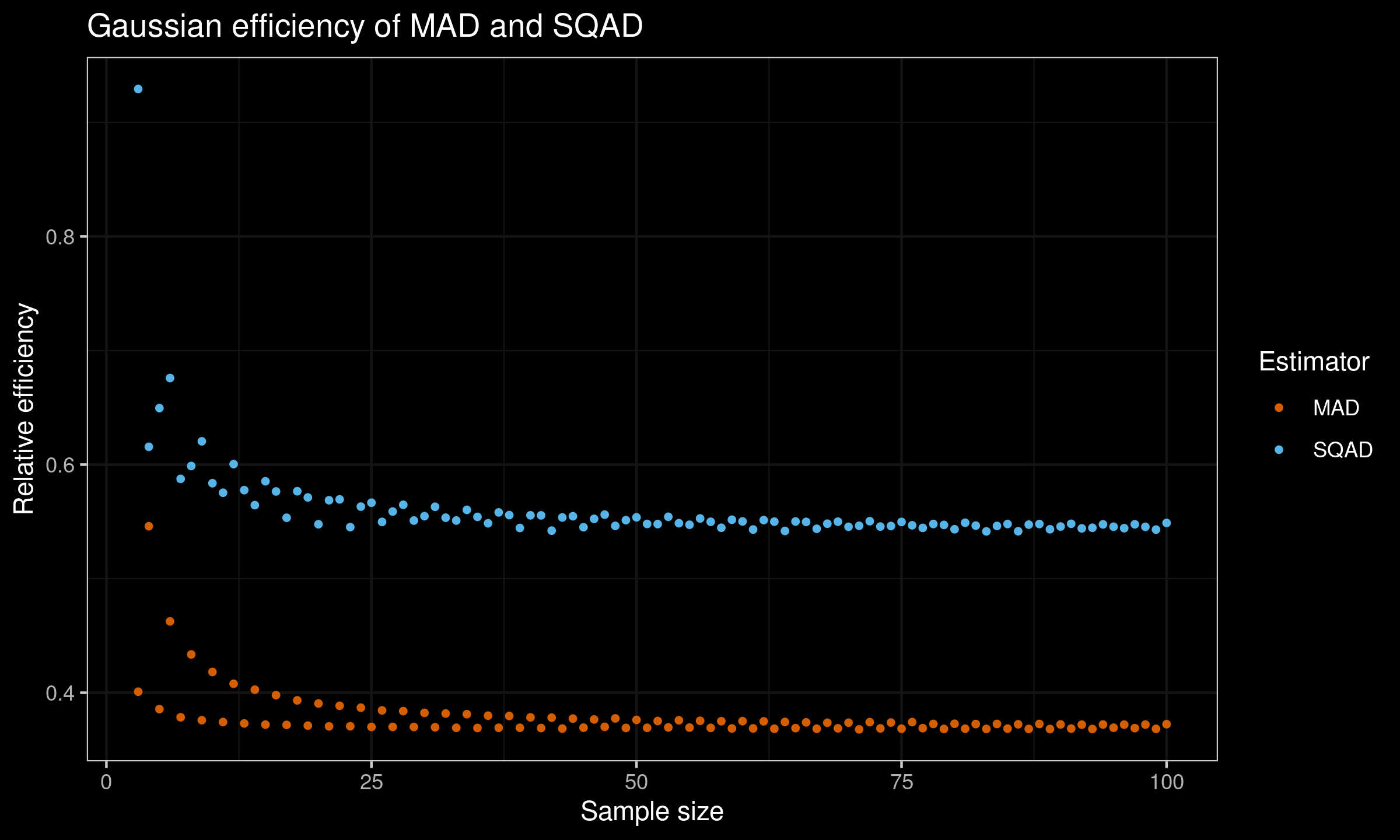

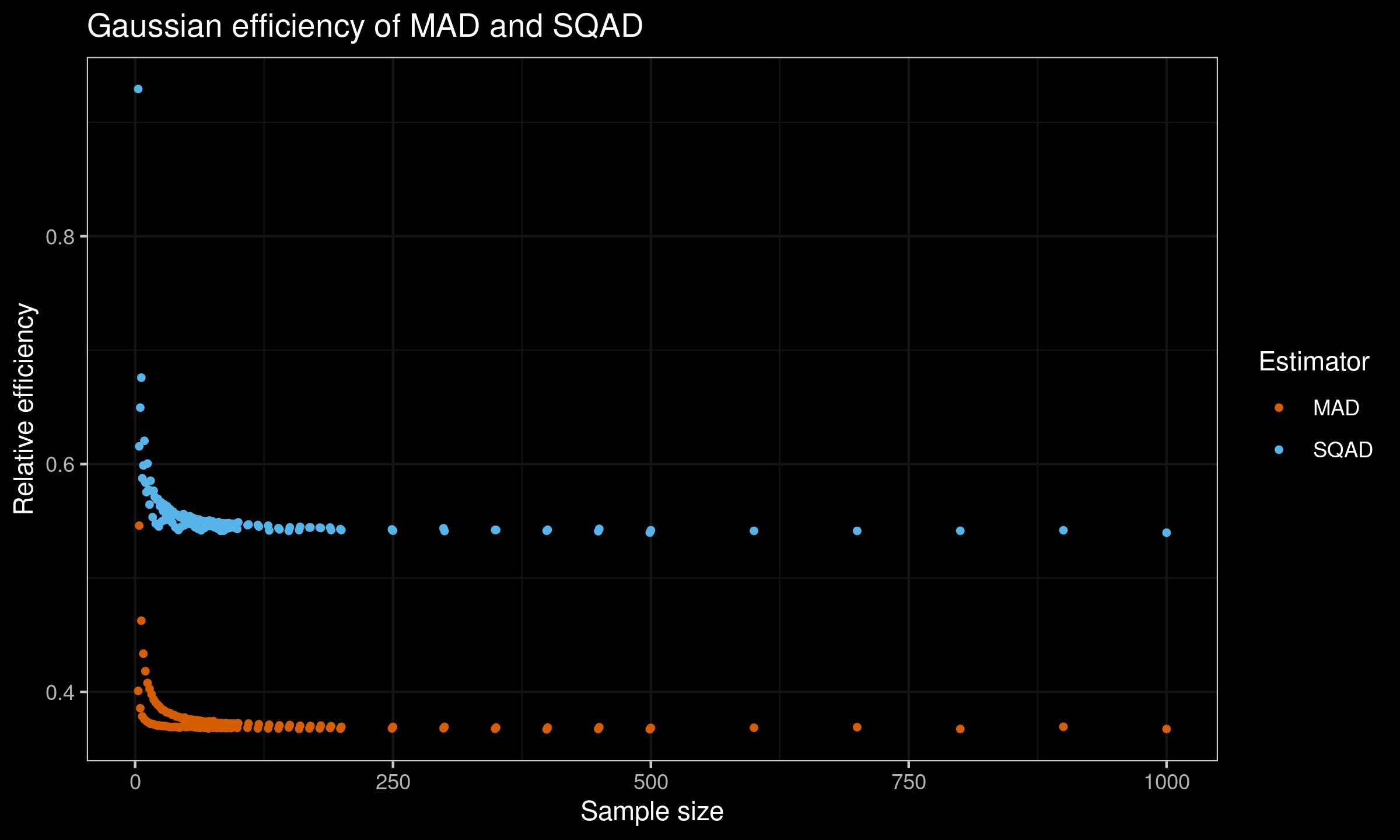

We perform one more simulation study to evaluate the Gaussian efficiency of $\SQAD$ and $\MAD$. As for the baseline, we consider the unbiased standard deviation $\SD_n$:

$$ \SD_n(X) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar{X})^2} \bigg/ c_4(n), \quad c_4(n) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{n-1}}\frac{\Gamma(\frac{n}{2})}{\Gamma(\frac{n-1}{2})}. $$The scheme of this simulation is straightforward: for each sample size $n$, we generate multiple random samples of the given size from the standard normal distribution. For an unbiased scale estimator $T_n$, we define the Gaussian efficiency as

$$ e(T_n) = \frac{\V[\SD_n]}{\V[T_n]}. $$Here is the plot of the efficiency values for $n \leq 100$:

And here is the raw efficiency values (including the obtained biases and the standardized variance values):

| n | eff.mad | eff.sqad |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.40085 | 0.92931 |

| 4 | 0.54596 | 0.61559 |

| 5 | 0.38562 | 0.64954 |

| 6 | 0.46252 | 0.67588 |

| 7 | 0.37846 | 0.58748 |

| 8 | 0.43354 | 0.59877 |

| 9 | 0.37588 | 0.62040 |

| 10 | 0.41818 | 0.58368 |

| 11 | 0.37429 | 0.57532 |

| 12 | 0.40784 | 0.60043 |

| 13 | 0.37305 | 0.57759 |

| 14 | 0.40263 | 0.56445 |

| 15 | 0.37202 | 0.58536 |

| 16 | 0.39787 | 0.57645 |

| 17 | 0.37180 | 0.55338 |

| 18 | 0.39328 | 0.57663 |

| 19 | 0.37113 | 0.57120 |

| 20 | 0.39053 | 0.54768 |

| 21 | 0.37051 | 0.56875 |

| 22 | 0.38851 | 0.56950 |

| 23 | 0.37061 | 0.54519 |

| 24 | 0.38686 | 0.56315 |

| 25 | 0.36999 | 0.56659 |

| 26 | 0.38448 | 0.54974 |

| 27 | 0.37002 | 0.55883 |

| 28 | 0.38386 | 0.56476 |

| 29 | 0.36996 | 0.55093 |

| 30 | 0.38231 | 0.55479 |

| 31 | 0.36968 | 0.56303 |

| 32 | 0.38174 | 0.55344 |

| 33 | 0.36925 | 0.55094 |

| 34 | 0.38118 | 0.56029 |

| 35 | 0.36908 | 0.55418 |

| 36 | 0.37986 | 0.54853 |

| 37 | 0.36925 | 0.55809 |

| 38 | 0.37960 | 0.55573 |

| 39 | 0.36926 | 0.54442 |

| 40 | 0.37839 | 0.55552 |

| 41 | 0.36904 | 0.55548 |

| 42 | 0.37812 | 0.54209 |

| 43 | 0.36856 | 0.55365 |

| 44 | 0.37729 | 0.55472 |

| 45 | 0.36934 | 0.54509 |

| 46 | 0.37655 | 0.55243 |

| 47 | 0.37010 | 0.55612 |

| 48 | 0.37746 | 0.54628 |

| 49 | 0.36910 | 0.55126 |

| 50 | 0.37615 | 0.55376 |

| 51 | 0.36922 | 0.54797 |

| 52 | 0.37519 | 0.54783 |

| 53 | 0.36956 | 0.55422 |

| 54 | 0.37582 | 0.54860 |

| 55 | 0.36941 | 0.54726 |

| 56 | 0.37536 | 0.55278 |

| 57 | 0.36917 | 0.54985 |

| 58 | 0.37500 | 0.54461 |

| 59 | 0.36867 | 0.55163 |

| 60 | 0.37506 | 0.55015 |

| 61 | 0.36870 | 0.54308 |

| 62 | 0.37489 | 0.55133 |

| 63 | 0.36841 | 0.54997 |

| 64 | 0.37435 | 0.54182 |

| 65 | 0.36894 | 0.55011 |

| 66 | 0.37401 | 0.54976 |

| 67 | 0.36843 | 0.54372 |

| 68 | 0.37368 | 0.54816 |

| 69 | 0.36877 | 0.54995 |

| 70 | 0.37373 | 0.54550 |

| 71 | 0.36787 | 0.54635 |

| 72 | 0.37420 | 0.55036 |

| 73 | 0.36872 | 0.54567 |

| 74 | 0.37385 | 0.54617 |

| 75 | 0.36847 | 0.54970 |

| 76 | 0.37425 | 0.54679 |

| 77 | 0.36892 | 0.54448 |

| 78 | 0.37262 | 0.54791 |

| 79 | 0.36825 | 0.54709 |

| 80 | 0.37277 | 0.54329 |

| 81 | 0.36844 | 0.54902 |

| 82 | 0.37253 | 0.54649 |

| 83 | 0.36827 | 0.54142 |

| 84 | 0.37260 | 0.54621 |

| 85 | 0.36851 | 0.54788 |

| 86 | 0.37232 | 0.54154 |

| 87 | 0.36828 | 0.54736 |

| 88 | 0.37260 | 0.54789 |

| 89 | 0.36819 | 0.54330 |

| 90 | 0.37219 | 0.54570 |

| 91 | 0.36857 | 0.54809 |

| 92 | 0.37199 | 0.54407 |

| 93 | 0.36819 | 0.54459 |

| 94 | 0.37212 | 0.54758 |

| 95 | 0.36929 | 0.54554 |

| 96 | 0.37203 | 0.54423 |

| 97 | 0.36895 | 0.54764 |

| 98 | 0.37204 | 0.54546 |

| 99 | 0.36833 | 0.54300 |

| 100 | 0.37240 | 0.54883 |

| 109 | 0.36846 | 0.54636 |

| 110 | 0.37218 | 0.54689 |

| 119 | 0.36797 | 0.54649 |

| 120 | 0.37157 | 0.54510 |

| 129 | 0.36793 | 0.54593 |

| 130 | 0.37119 | 0.54175 |

| 139 | 0.36784 | 0.54373 |

| 140 | 0.37056 | 0.54266 |

| 149 | 0.36879 | 0.54139 |

| 150 | 0.37090 | 0.54441 |

| 159 | 0.36752 | 0.54201 |

| 160 | 0.37026 | 0.54493 |

| 169 | 0.36796 | 0.54429 |

| 170 | 0.37005 | 0.54434 |

| 179 | 0.36794 | 0.54417 |

| 180 | 0.37034 | 0.54388 |

| 189 | 0.36822 | 0.54427 |

| 190 | 0.36989 | 0.54206 |

| 199 | 0.36770 | 0.54290 |

| 200 | 0.36926 | 0.54206 |

| 249 | 0.36793 | 0.54262 |

| 250 | 0.36917 | 0.54152 |

| 299 | 0.36802 | 0.54363 |

| 300 | 0.36926 | 0.54122 |

| 349 | 0.36763 | 0.54216 |

| 350 | 0.36865 | 0.54212 |

| 399 | 0.36709 | 0.54143 |

| 400 | 0.36864 | 0.54230 |

| 449 | 0.36743 | 0.54104 |

| 450 | 0.36892 | 0.54312 |

| 499 | 0.36719 | 0.53987 |

| 500 | 0.36840 | 0.54189 |

| 600 | 0.36851 | 0.54134 |

| 700 | 0.36897 | 0.54134 |

| 800 | 0.36744 | 0.54142 |

| 900 | 0.36934 | 0.54187 |

| 1000 | 0.36741 | 0.53976 |

| 1500 | 0.36821 | 0.54124 |

| 2000 | 0.36836 | 0.54144 |

| 3000 | 0.36810 | 0.54149 |

| 10000 | 0.36782 | 0.54066 |

| 50000 | 0.36810 | 0.54080 |

According to this simulation study, the Gaussian efficiency of $\SQAD$ is $\approx 54\%$.

Asymptotic efficiency of SQAD

We already know the equation for the Gaussian efficiency of $\QAD$:

$$ \lim_{n \to \infty} e(\QAD_n(X, p),\; \SD_n(X)) = \Bigg( \pi p(1-p) \exp\Big(2\big(\erfinv(p) \big)^2 \Big) \Bigg)^{-1}. $$To adopt this equation for $\SQAD$, we should put $p = \Phi(1) - \Phi(-1)$.

Since $\Phi(1) = (1 + \erf(1/\sqrt{2})) / 2$, we can write

$$ \erf(1/\sqrt{2}) = 2\Phi(1) - 1 = \Phi(1) - \Phi(-1), $$which is the same as

$$ 2\Big(\erfinv(\Phi(1) - \Phi(-1)) \Big)^2 = 1. $$This gives us a simple expression for the Gaussian efficiency of $\SQAD_n(X)$:

$$ \lim_{n \to \infty} e(\SQAD_n(X),\; \SD_n(X)) = \Big( \pi e \cdot (\Phi(1)-\Phi(-1)) \cdot (1-\Phi(1)+\Phi(-1)) \Big)^{-1} \approx 0.540565. $$Summary

In this post, we discussed a new measure of statistical dispersion called the standard quantile absolute deviation ($\SQAD$) which is consistent with the standard deviation under normality. Its breakdown point is $\approx 31.73\%$. When such robustness is enough, $\SQAD$ can be a decent replacement for the median absolute deviation because it has higher statistical efficiency ($\approx 54\%$).

References

- [Hyndman1996]

Hyndman, R. J. and Fan, Y. 1996. Sample quantiles in statistical packages, American Statistician 50, 361–365.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2684934 - [Harrell1982]

Harrell, F.E. and Davis, C.E., 1982. A new distribution-free quantile estimator. Biometrika, 69(3), pp.635-640.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1a48/9bb74293753023c5bb6bff8e41e8fe68060f.pdf - [Akinshin2022]

Andrey Akinshin (2022) Trimmed Harrell-Davis quantile estimator based on the highest density interval of the given width, Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03610918.2022.2050396 - [Arnold2008]

Arnold, Barry C., N. Balakrishnan, and H. N. Nagaraja. A First Course in Order Statistics. Classics in Applied Mathematics 54. Philadelphia, PA: SIAM, 2008.