Unbiased median absolute deviation based on the Harrell-Davis quantile estimator

The below text contains an intermediate snapshot of the research and is preserved for historical purposes.

The median absolute deviation ($\textrm{MAD}$) is a robust measure of scale. In the previous post, I showed how to use the unbiased version of the $\textrm{MAD}$ estimator as a robust alternative to the standard deviation. “Unbiasedness” means that such estimator’s expected value equals the true value of the standard deviation. Unfortunately, there is such thing as the bias–variance tradeoff: when we remove the bias of the $\textrm{MAD}$ estimator, we increase its variance and mean squared error ($\textrm{MSE}$).

In this post, I want to suggest a more efficient unbiased $\textrm{MAD}$ estimator. It’s also a consistent estimator for the standard deviation, but it has smaller $\textrm{MSE}$. To build this estimator, we should replace the classic “straightforward” median estimator with the Harrell-Davis quantile estimator and adjust bias-correction factors. Let’s discuss this approach in detail.

Introduction

Let’s consider a sample $x = \{ x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n \}$. Its median absolute deviation $\textrm{MAD}_n$ can be defined as follows:

$$ \textrm{MAD}_n = C_n \cdot \textrm{median}(|X - \textrm{median}(X)|) $$where $\textrm{median}$ is a median estimator, $C_n$ is a scale factor (or consistency constant).

Typically, $\textrm{median}$ assumes the classic “straightforward” median estimator:

- If $n$ is odd, the median is the middle element of the sorted sample

- If $n$ is even, the median is the arithmetic average of the two middle elements of the sorted sample

However, we can use other median estimators.

Let’s consider $\textrm{median}_{\textrm{HD}}$ which calculates the median using the Harrell-Davis quantile estimator (see A new distribution-free quantile estimator

By Frank E Harrell, C E Davis

·

1982harrell1982):

where $I_t(a, b)$ denotes the regularized incomplete beta function.

When $n \to \infty$, we have the exact value of $C_n$ which makes $\textrm{MAD}_n$ an unbiased estimator for the standard deviation:

$$ C_n = C_\infty = \dfrac{1}{\Phi^{-1}(3/4)} \approx 1.4826022185056 $$For finite values of $n$, we should use adjusted $C_n$ values.

We already discussed these values for the straightforward median estimator in

the previous post

(this problem is well-covered in Investigation of finite-sample properties of robust location and scale estimators

By Chanseok Park, Haewon Kim, Min Wang

·

2020park2020).

For $\textrm{median}_{\textrm{HD}}$, we should use another set of $C_n$ values.

We reuse the approach from Finite-Sample Bias-Correction Factors for the Median Absolute Deviation

By Kevin Hayes

·

2014hayes2014 with the following notation:

Factors for small n

Factors for the small values of $n$ can be obtained using numerical experiments. Here is the scheme for the performed simulation:

- Enumerate $n$ from $2$ to $100$

- For each $n$, generate $2\cdot 10^8$ samples from the normal distribution of size $n$ (the Box–Muller transform is used, see [Box1958])

- For each sample, estimate $\textrm{MAD}_n$ using $C_n = 1$

- Calculate the arithmetic average of all $\textrm{MAD}_n$ values for the same $n$: the result is the value of $\hat{a}_n$

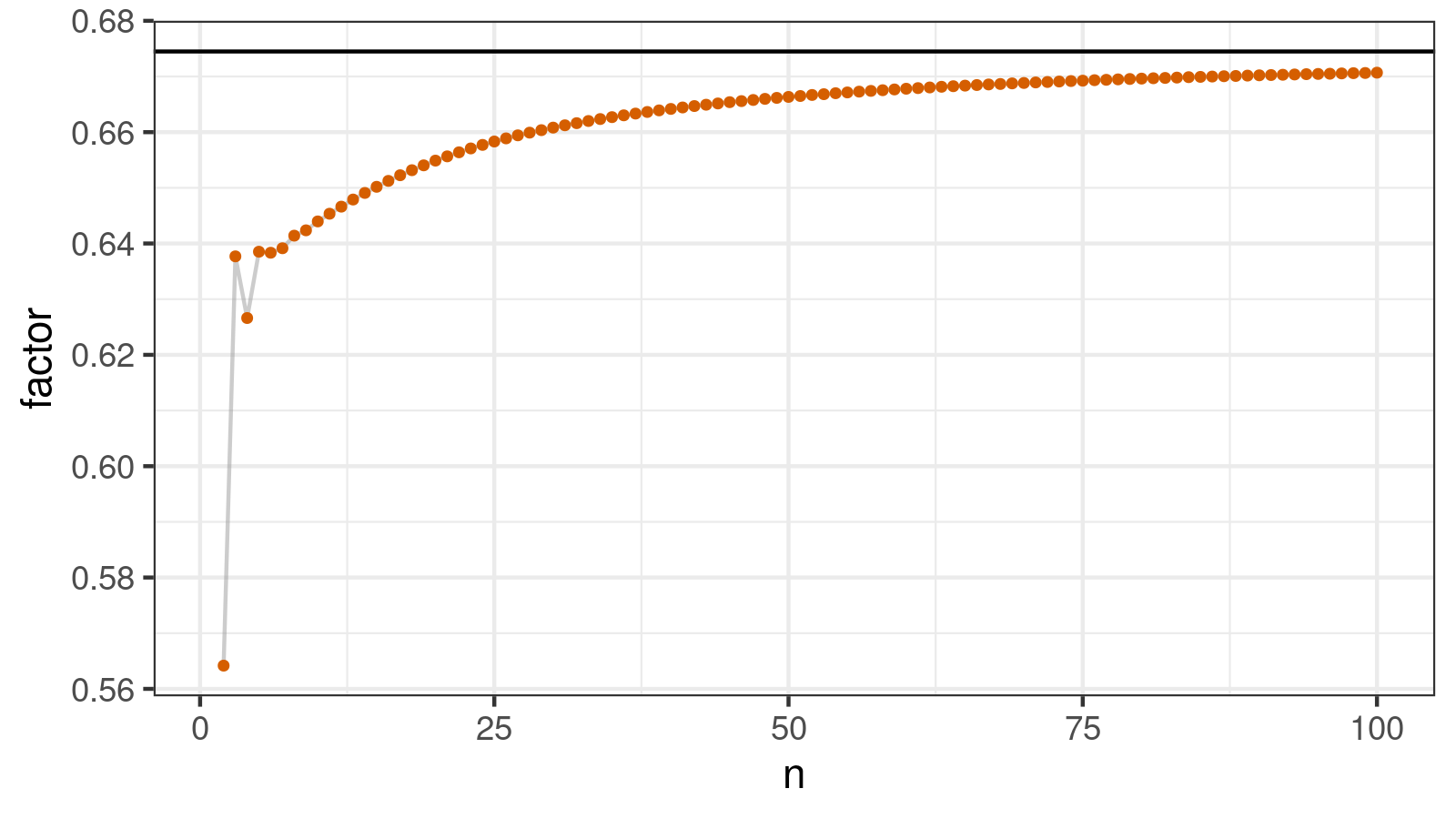

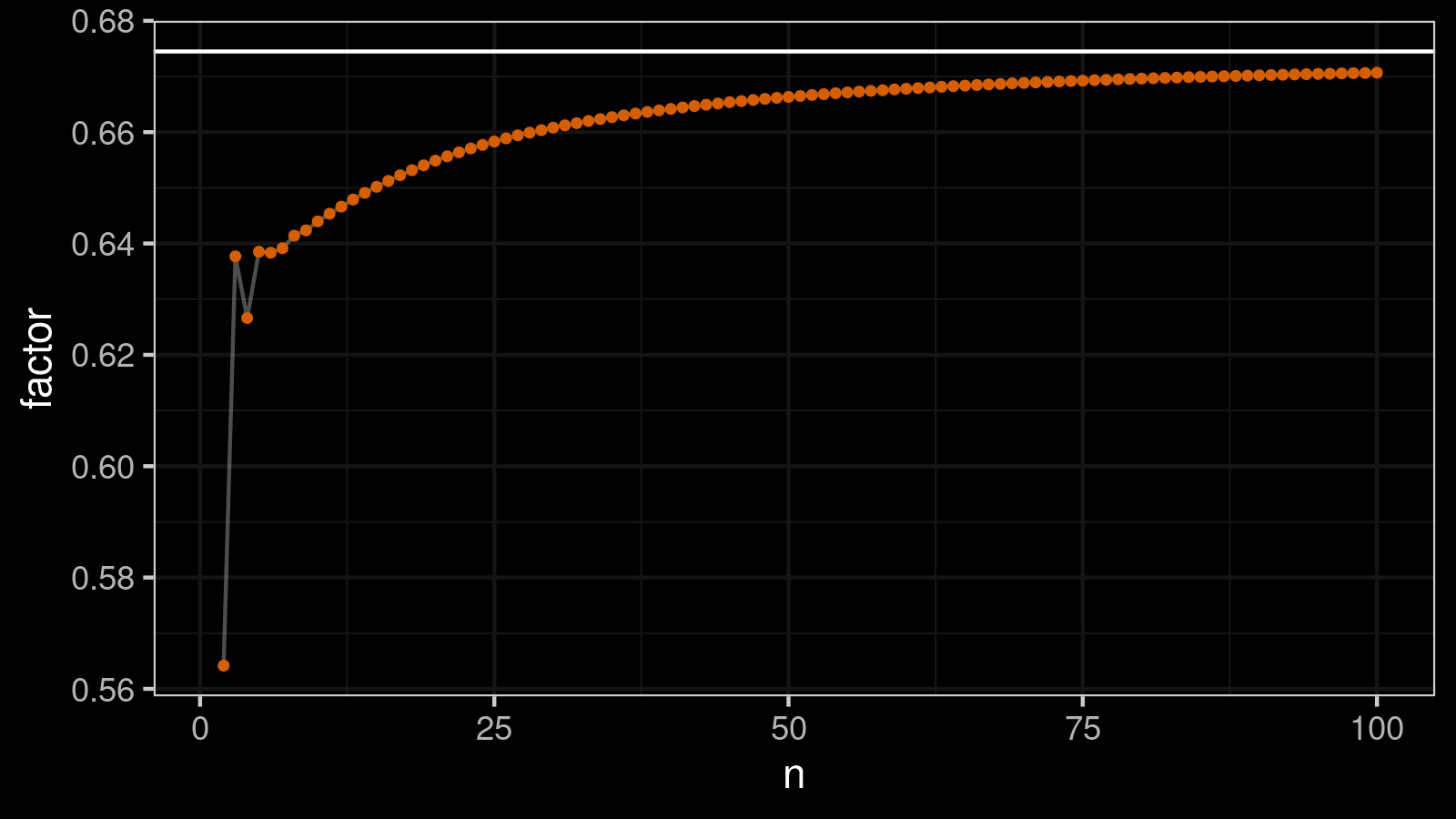

As the result of this simulation, I got the following table with $\hat{a}_n$ and $C_n$ values for $n \in \{ 2..100 \}$.

| $n$ | $\hat{a}_n$ | $C_n$ | $n$ | $\hat{a}_n$ | $C_n$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NA | NA | 51 | 0.66649 | 1.50039 |

| 2 | 0.56417 | 1.77250 | 52 | 0.66668 | 1.49998 |

| 3 | 0.63769 | 1.56816 | 53 | 0.66682 | 1.49966 |

| 4 | 0.62661 | 1.59589 | 54 | 0.66699 | 1.49926 |

| 5 | 0.63853 | 1.56611 | 55 | 0.66713 | 1.49895 |

| 6 | 0.63834 | 1.56656 | 56 | 0.66728 | 1.49863 |

| 7 | 0.63915 | 1.56458 | 57 | 0.66741 | 1.49833 |

| 8 | 0.64141 | 1.55908 | 58 | 0.66753 | 1.49805 |

| 9 | 0.64237 | 1.55675 | 59 | 0.66767 | 1.49774 |

| 10 | 0.64397 | 1.55288 | 60 | 0.66780 | 1.49746 |

| 11 | 0.64535 | 1.54955 | 61 | 0.66791 | 1.49720 |

| 12 | 0.64662 | 1.54651 | 62 | 0.66803 | 1.49694 |

| 13 | 0.64790 | 1.54346 | 63 | 0.66815 | 1.49667 |

| 14 | 0.64908 | 1.54064 | 64 | 0.66825 | 1.49644 |

| 15 | 0.65018 | 1.53803 | 65 | 0.66836 | 1.49621 |

| 16 | 0.65125 | 1.53552 | 66 | 0.66846 | 1.49597 |

| 17 | 0.65226 | 1.53313 | 67 | 0.66857 | 1.49574 |

| 18 | 0.65317 | 1.53101 | 68 | 0.66865 | 1.49555 |

| 19 | 0.65404 | 1.52896 | 69 | 0.66876 | 1.49531 |

| 20 | 0.65489 | 1.52698 | 70 | 0.66883 | 1.49514 |

| 21 | 0.65565 | 1.52520 | 71 | 0.66893 | 1.49493 |

| 22 | 0.65638 | 1.52351 | 72 | 0.66901 | 1.49475 |

| 23 | 0.65708 | 1.52190 | 73 | 0.66910 | 1.49456 |

| 24 | 0.65771 | 1.52043 | 74 | 0.66918 | 1.49437 |

| 25 | 0.65832 | 1.51902 | 75 | 0.66925 | 1.49422 |

| 26 | 0.65888 | 1.51772 | 76 | 0.66933 | 1.49402 |

| 27 | 0.65943 | 1.51647 | 77 | 0.66940 | 1.49387 |

| 28 | 0.65991 | 1.51536 | 78 | 0.66948 | 1.49370 |

| 29 | 0.66036 | 1.51433 | 79 | 0.66955 | 1.49354 |

| 30 | 0.66082 | 1.51328 | 80 | 0.66962 | 1.49339 |

| 31 | 0.66123 | 1.51233 | 81 | 0.66968 | 1.49325 |

| 32 | 0.66161 | 1.51146 | 82 | 0.66974 | 1.49312 |

| 33 | 0.66200 | 1.51057 | 83 | 0.66980 | 1.49298 |

| 34 | 0.66235 | 1.50977 | 84 | 0.66988 | 1.49281 |

| 35 | 0.66270 | 1.50899 | 85 | 0.66993 | 1.49270 |

| 36 | 0.66302 | 1.50824 | 86 | 0.66999 | 1.49257 |

| 37 | 0.66334 | 1.50753 | 87 | 0.67005 | 1.49244 |

| 38 | 0.66362 | 1.50688 | 88 | 0.67009 | 1.49233 |

| 39 | 0.66391 | 1.50623 | 89 | 0.67016 | 1.49219 |

| 40 | 0.66417 | 1.50563 | 90 | 0.67021 | 1.49207 |

| 41 | 0.66443 | 1.50504 | 91 | 0.67026 | 1.49196 |

| 42 | 0.66469 | 1.50447 | 92 | 0.67031 | 1.49185 |

| 43 | 0.66493 | 1.50393 | 93 | 0.67036 | 1.49174 |

| 44 | 0.66515 | 1.50341 | 94 | 0.67041 | 1.49161 |

| 45 | 0.66539 | 1.50289 | 95 | 0.67046 | 1.49152 |

| 46 | 0.66557 | 1.50246 | 96 | 0.67049 | 1.49144 |

| 47 | 0.66578 | 1.50200 | 97 | 0.67055 | 1.49131 |

| 48 | 0.66598 | 1.50155 | 98 | 0.67060 | 1.49121 |

| 49 | 0.66616 | 1.50115 | 99 | 0.67063 | 1.49114 |

| 50 | 0.66633 | 1.50076 | 100 | 0.67068 | 1.49102 |

Here is a visualization of this table:

Factors for huge n

To build the equation for $n > 100$, we also continue the approach suggested in Finite-Sample Bias-Correction Factors for the Median Absolute Deviation

By Kevin Hayes

·

2014hayes2014 (pages 2208-2209)

and use the prediction equation of the following form:

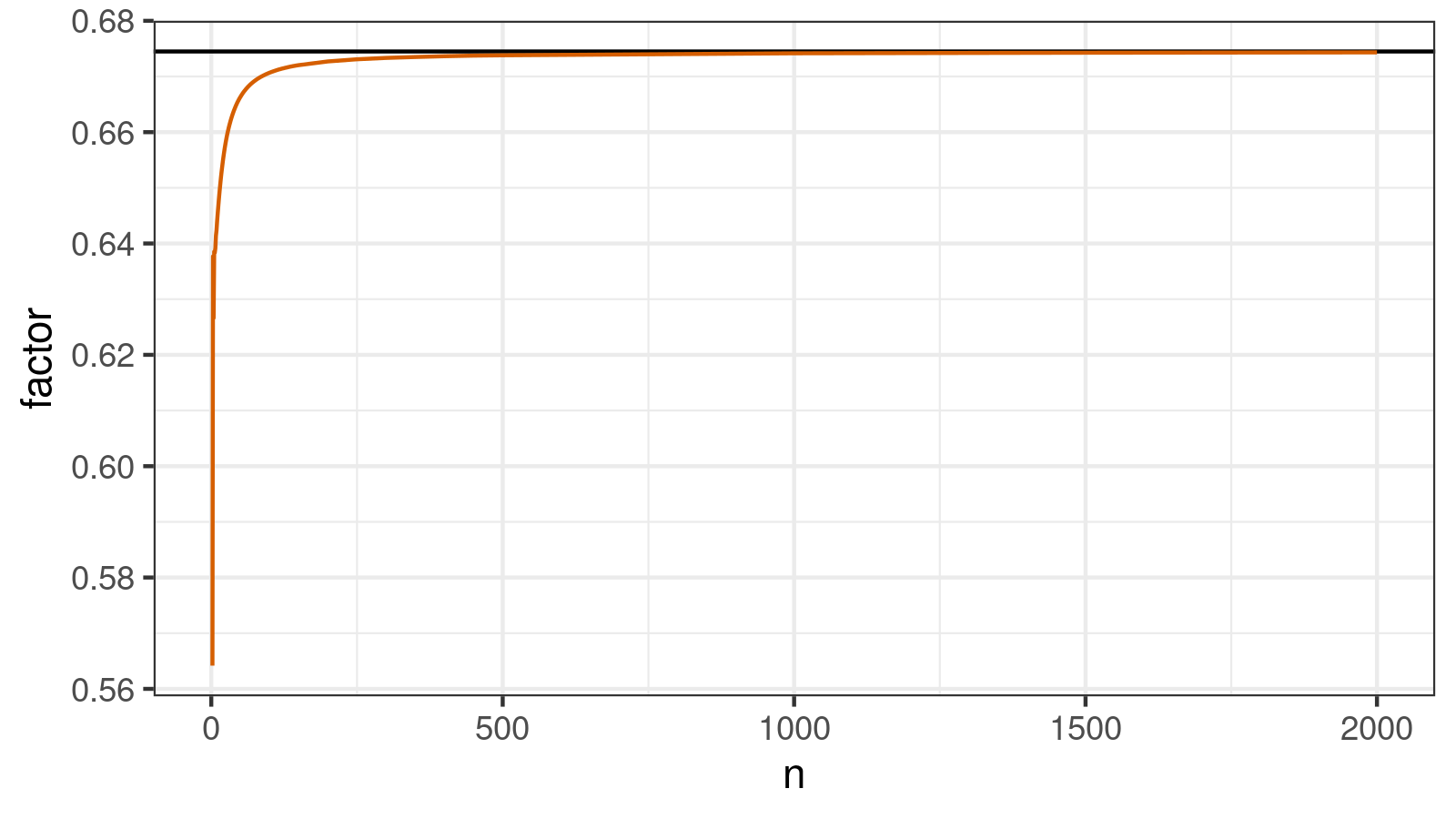

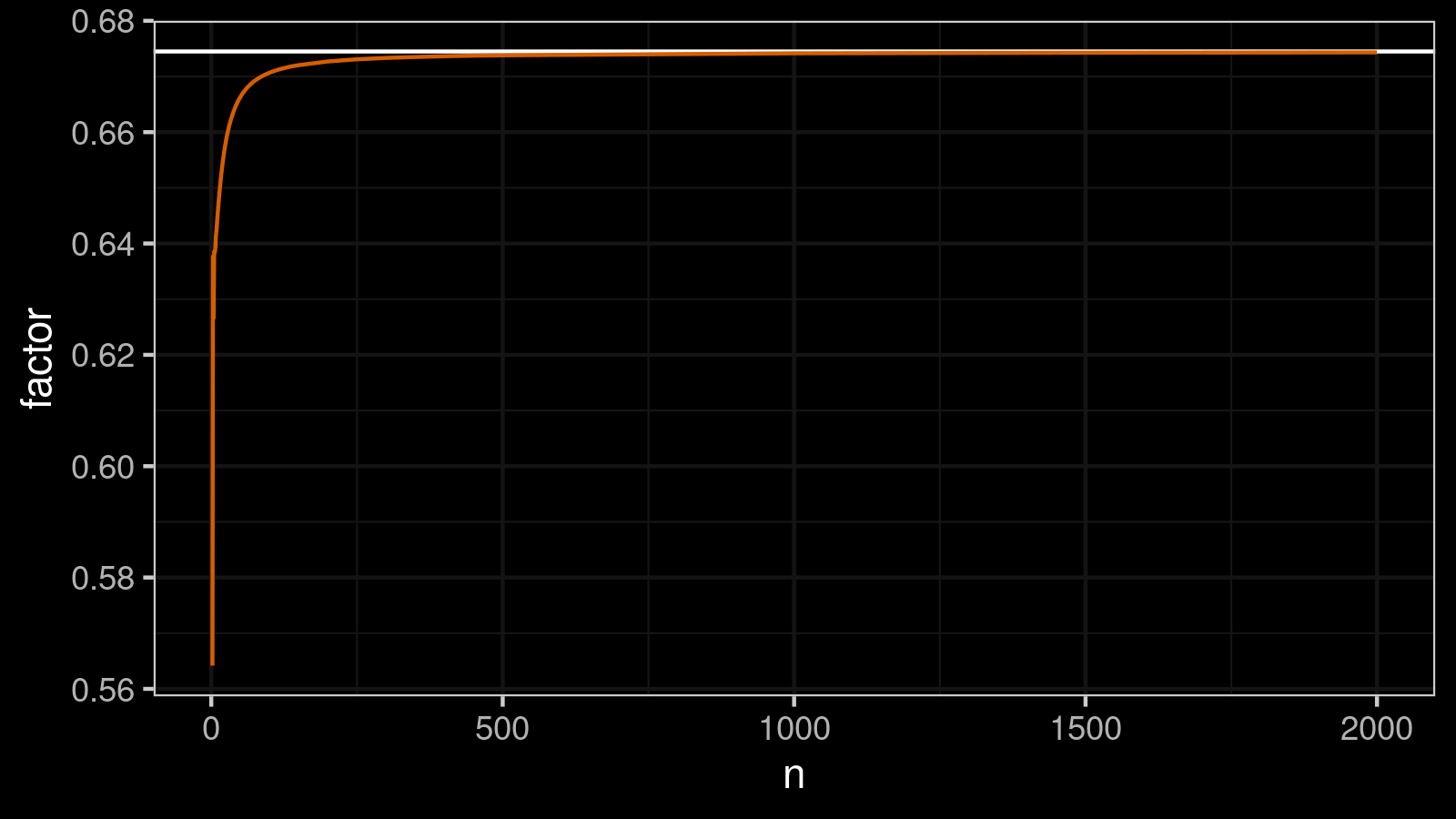

We simulated approximations of $\hat{a}_n$ for some large $n$ values:

| $n$ | $\hat{a}_n$ |

|---|---|

| 100 | 0.6707 |

| 110 | 0.6711 |

| 120 | 0.6714 |

| 130 | 0.6716 |

| 140 | 0.6719 |

| 150 | 0.6720 |

| 200 | 0.6727 |

| 250 | 0.6731 |

| 300 | 0.6733 |

| 350 | 0.6735 |

| 400 | 0.6736 |

| 450 | 0.6737 |

| 500 | 0.6738 |

| 1000 | 0.6742 |

| 1500 | 0.6743 |

| 2000 | 0.6743 |

Next, we fitted these values using the multiple linear regression. The dependent variable is $y = 1 - \hat{a}_n / \Phi^{-1}(3/4)$; the independent variables are $n^{-1}$ and $n^{-2}$; the intercept is zero:

$$ y = \alpha n^{-1} + \beta n^{-2}. $$The fitted model was adjusted a little bit to get nice-looking values (keeping the good accuracy level):

$$ \alpha = 0.5,\quad \beta = 6.5. $$These values give pretty accurate estimation of $\hat{a}_n$ for $n > 100$ (the accuracy is less than $10^{-4}$).

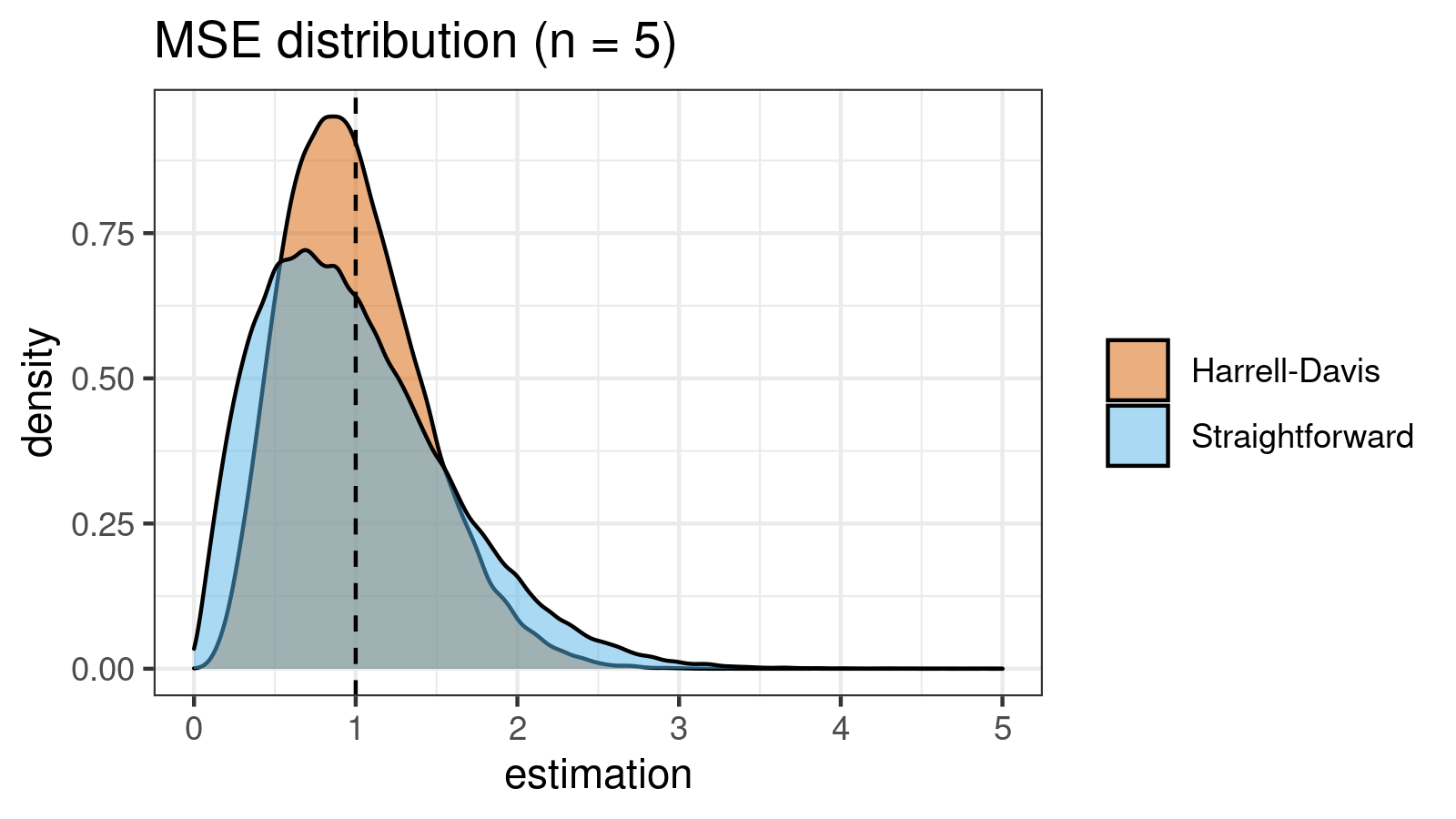

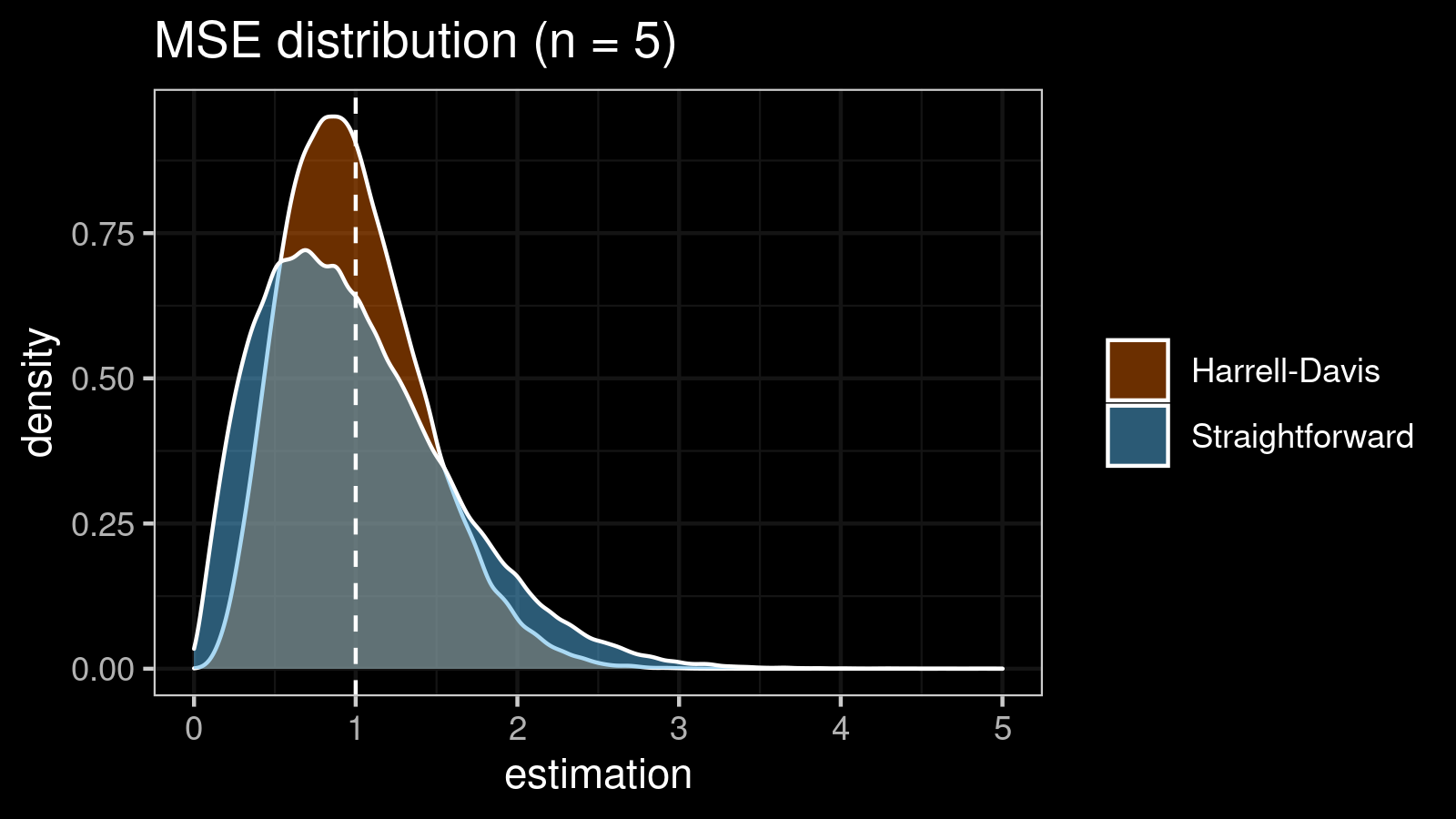

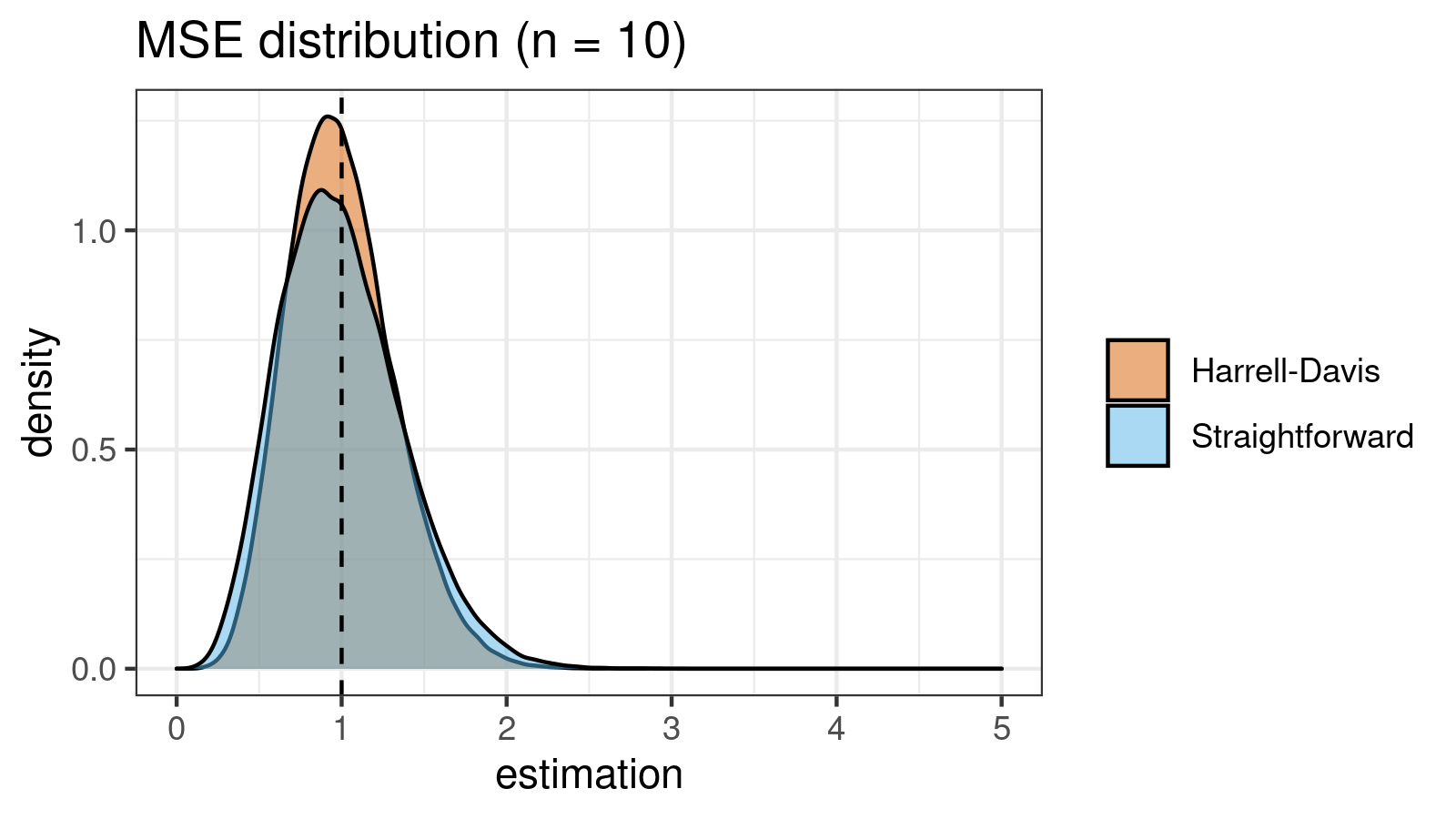

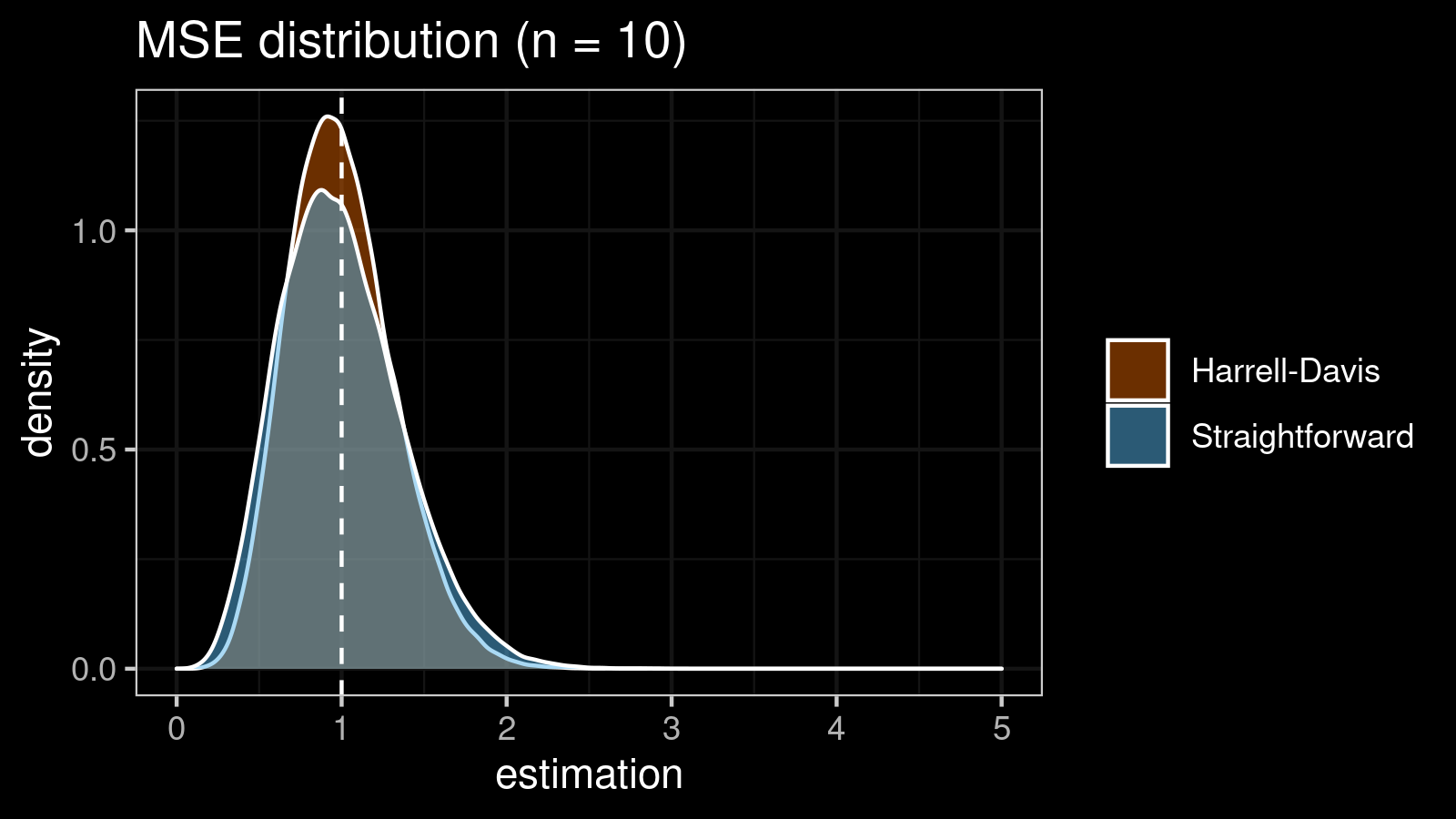

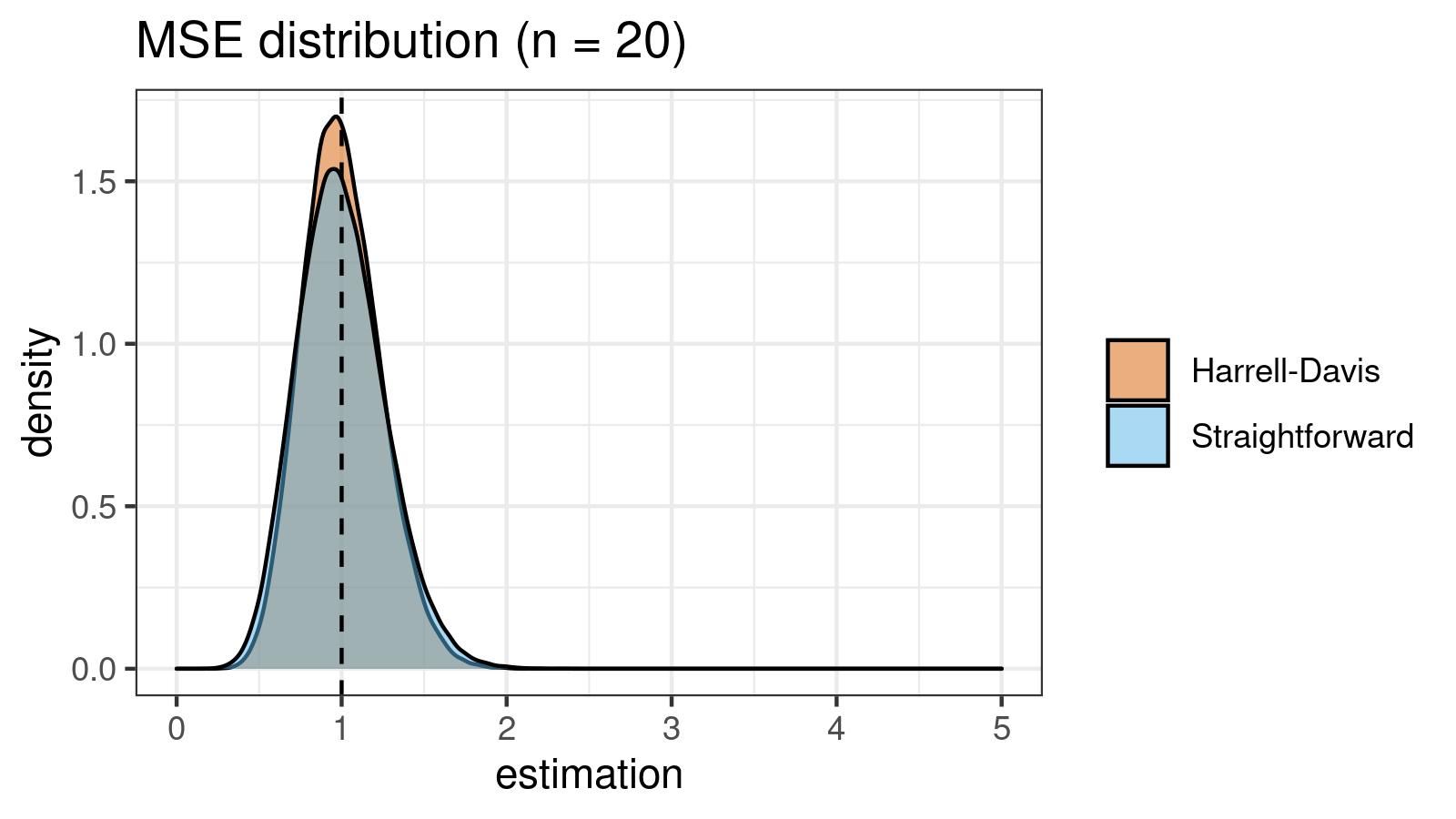

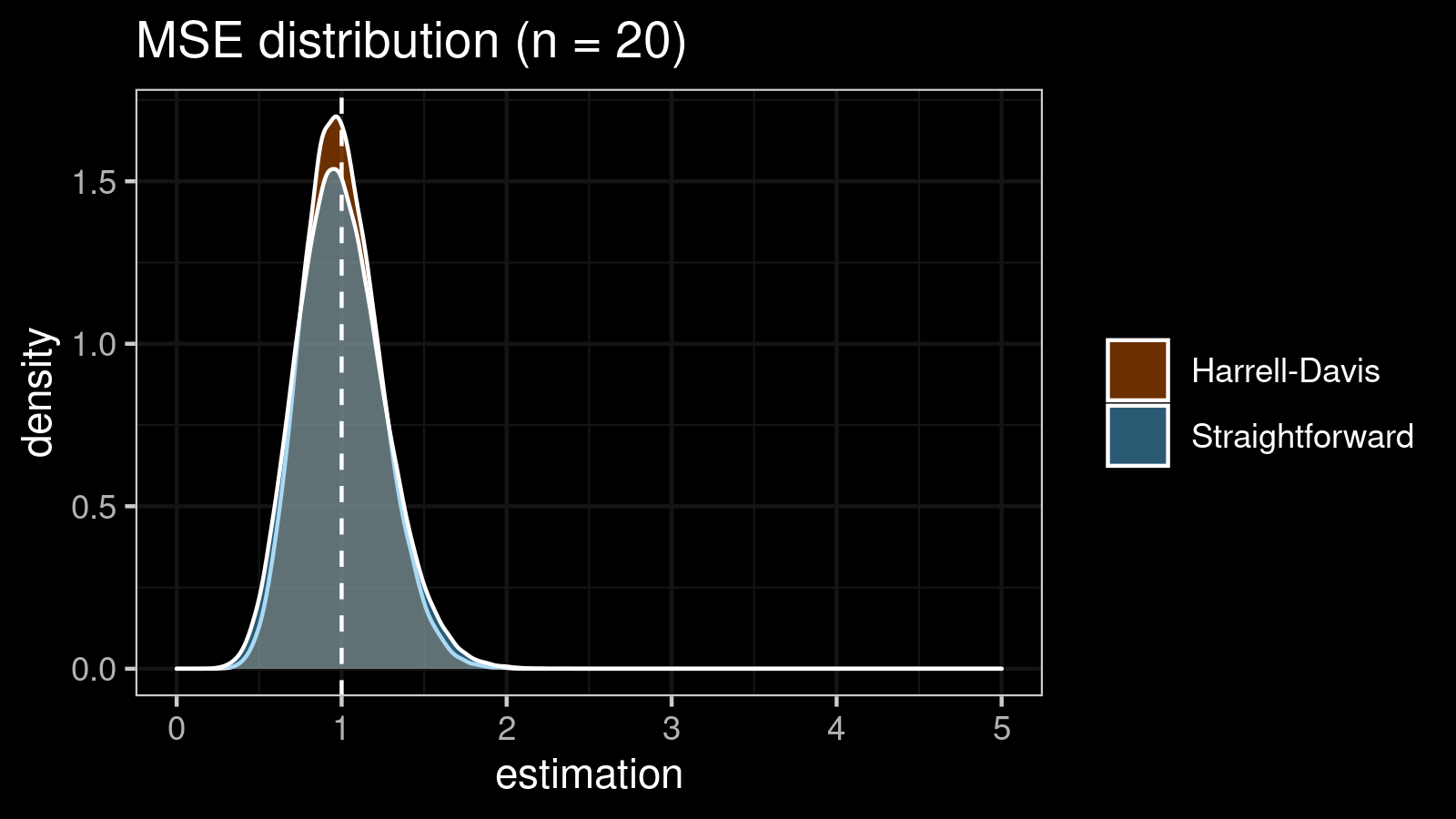

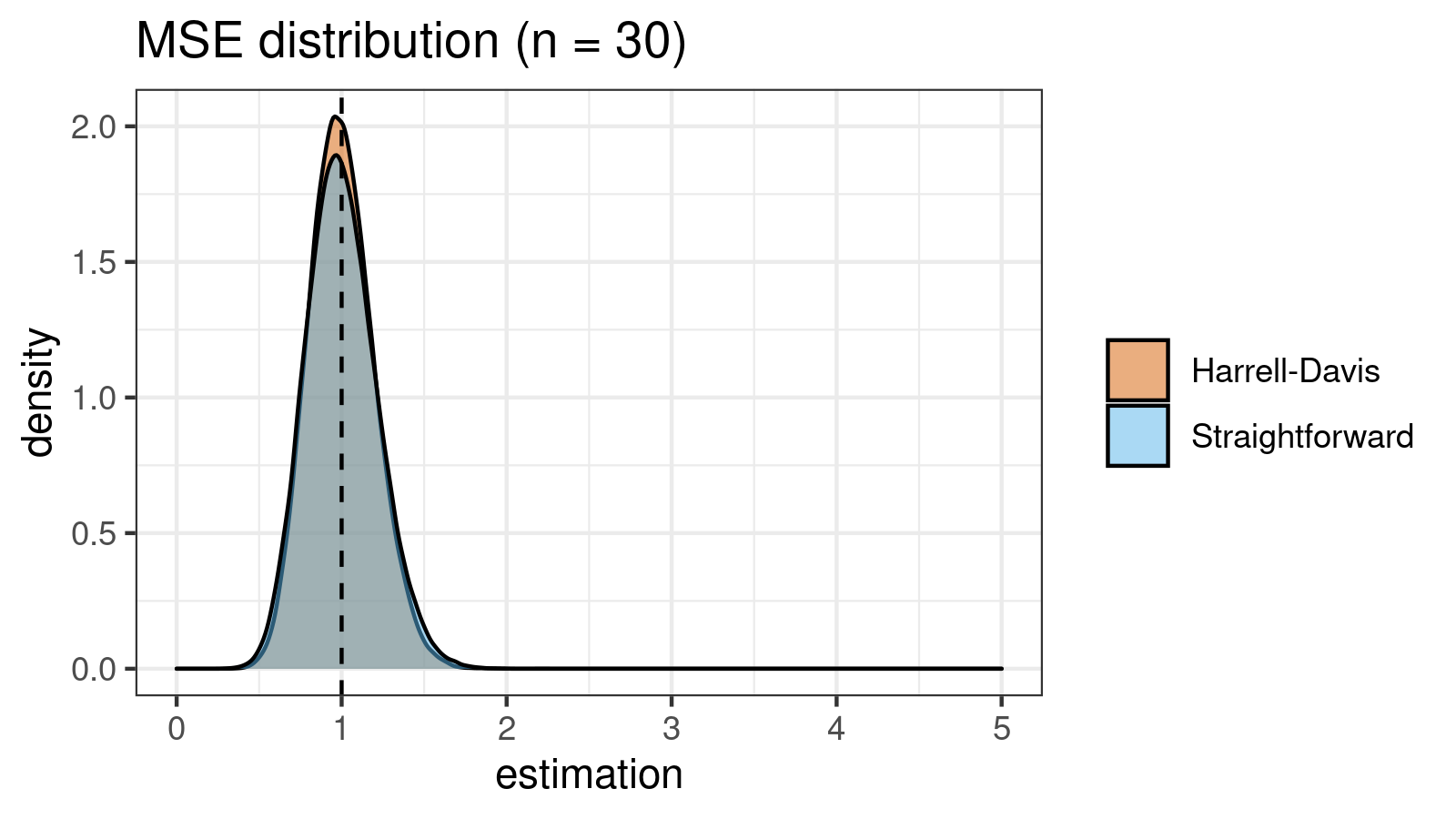

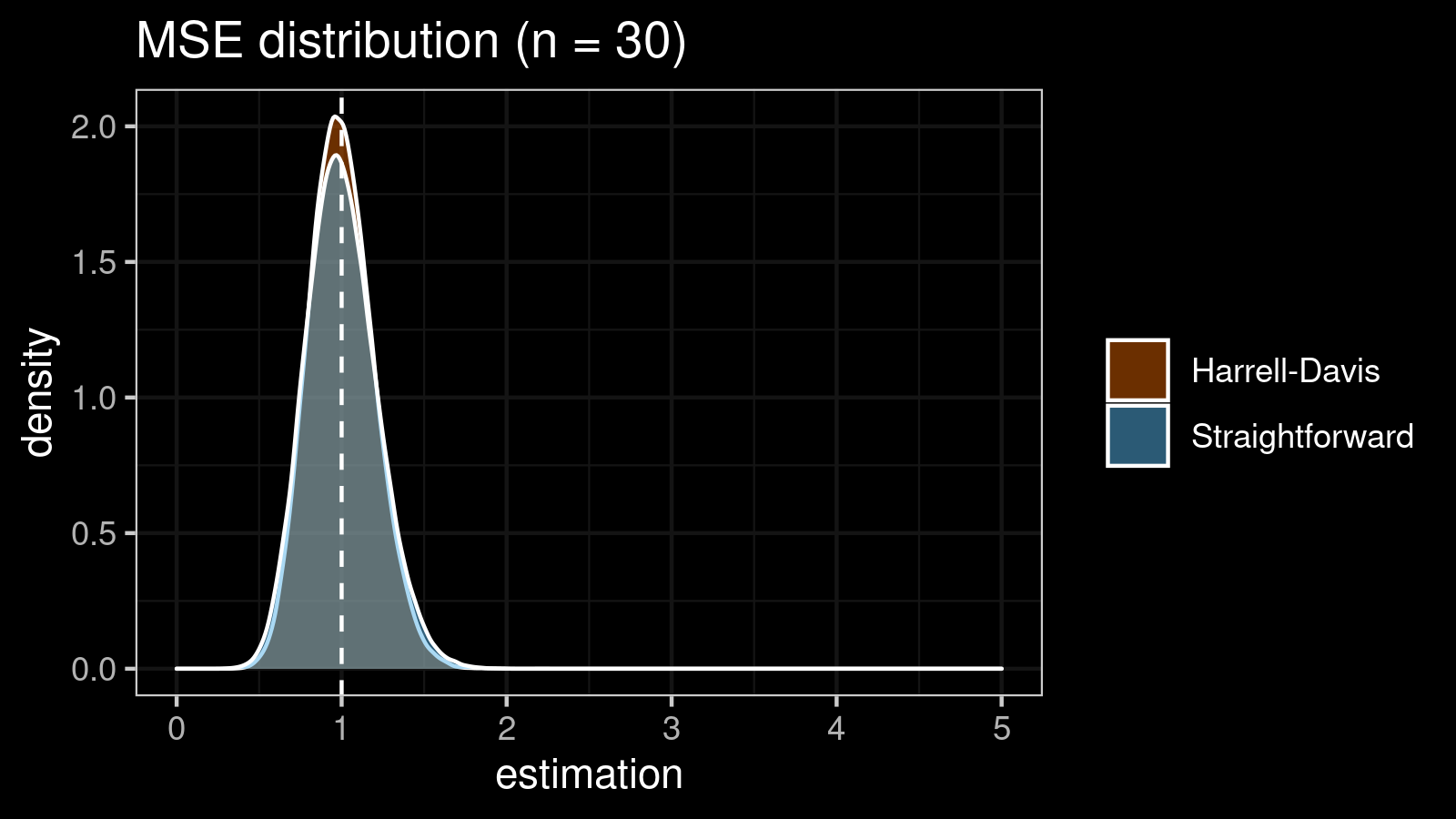

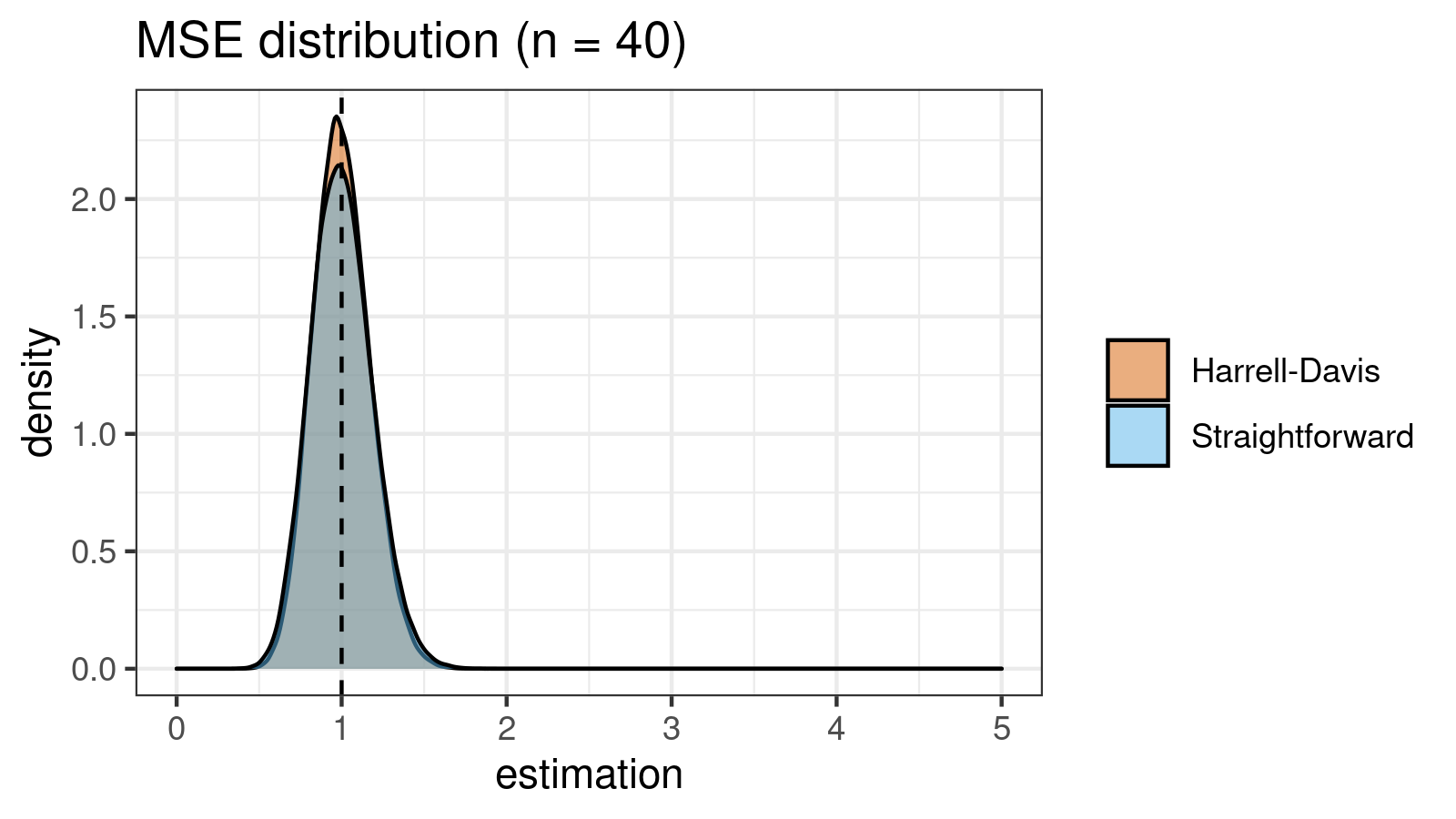

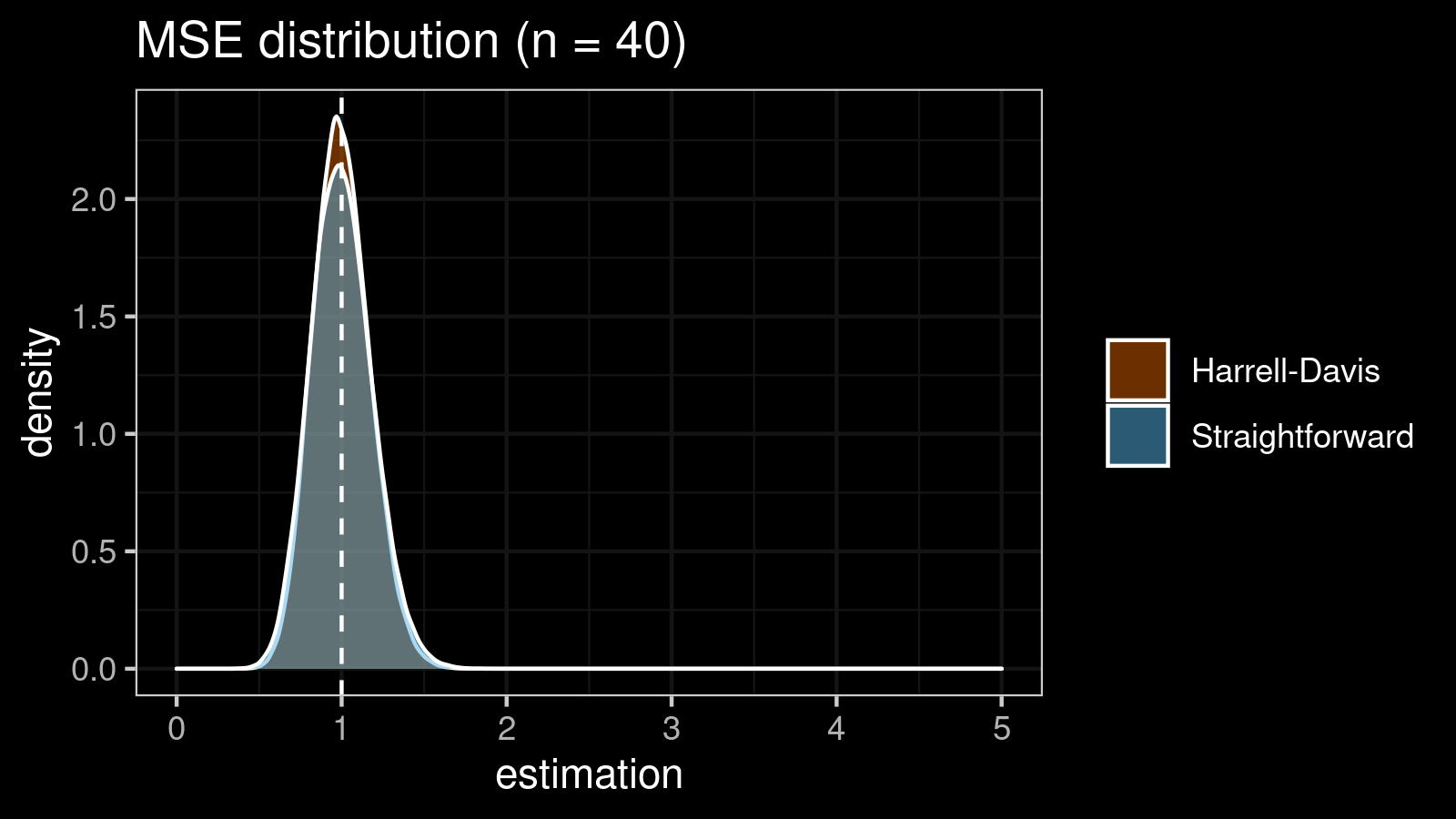

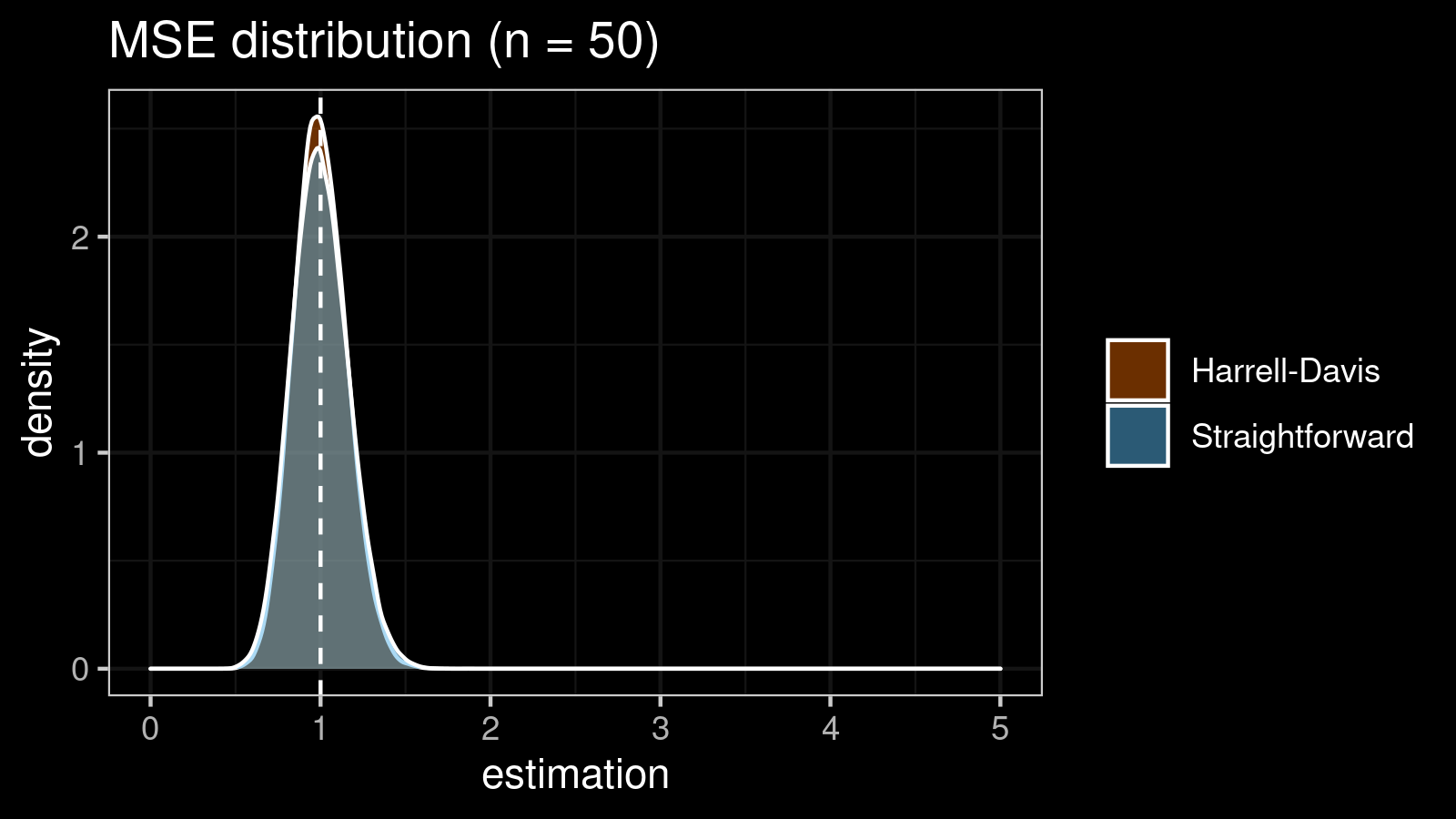

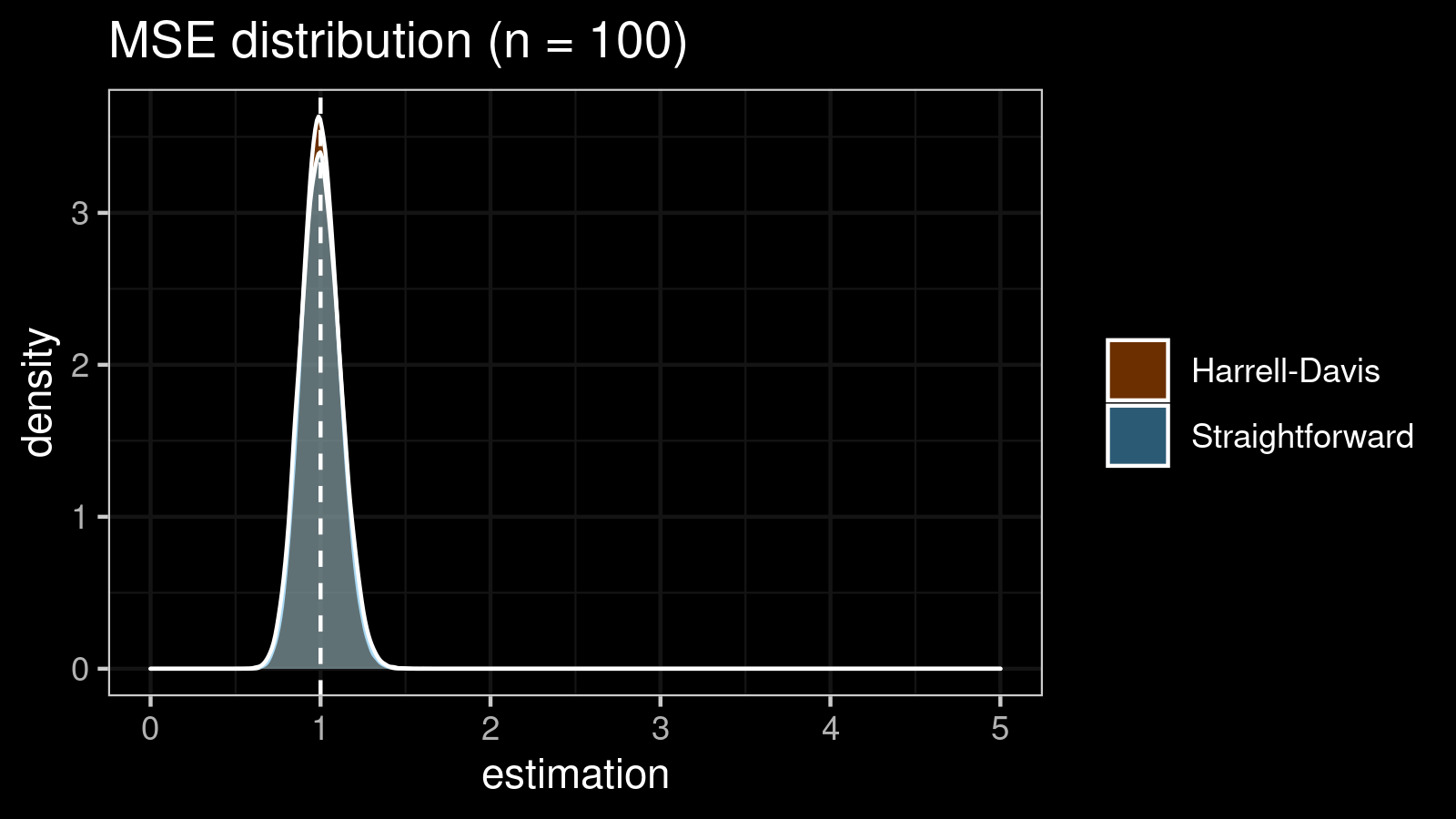

The mean squared error

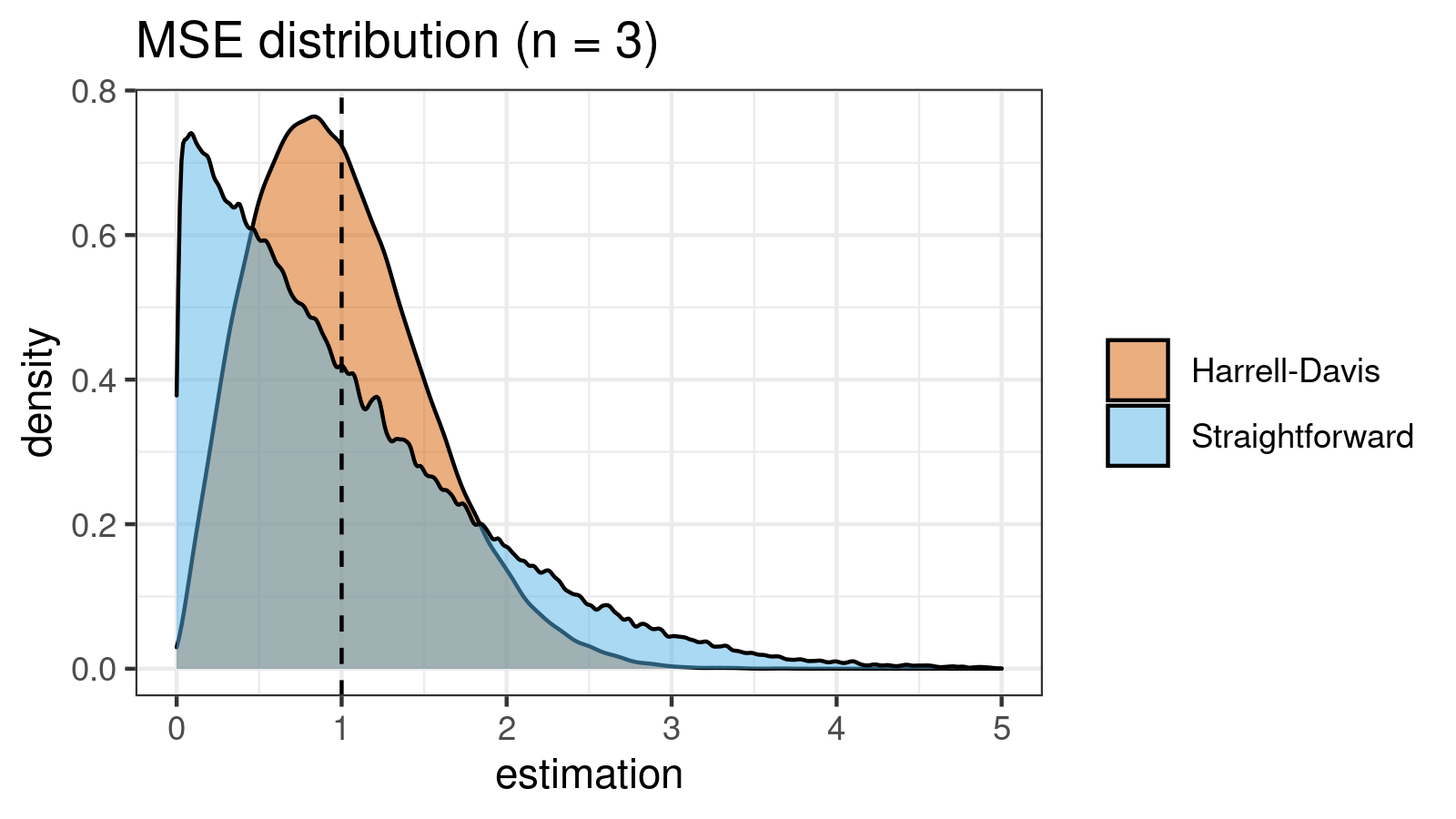

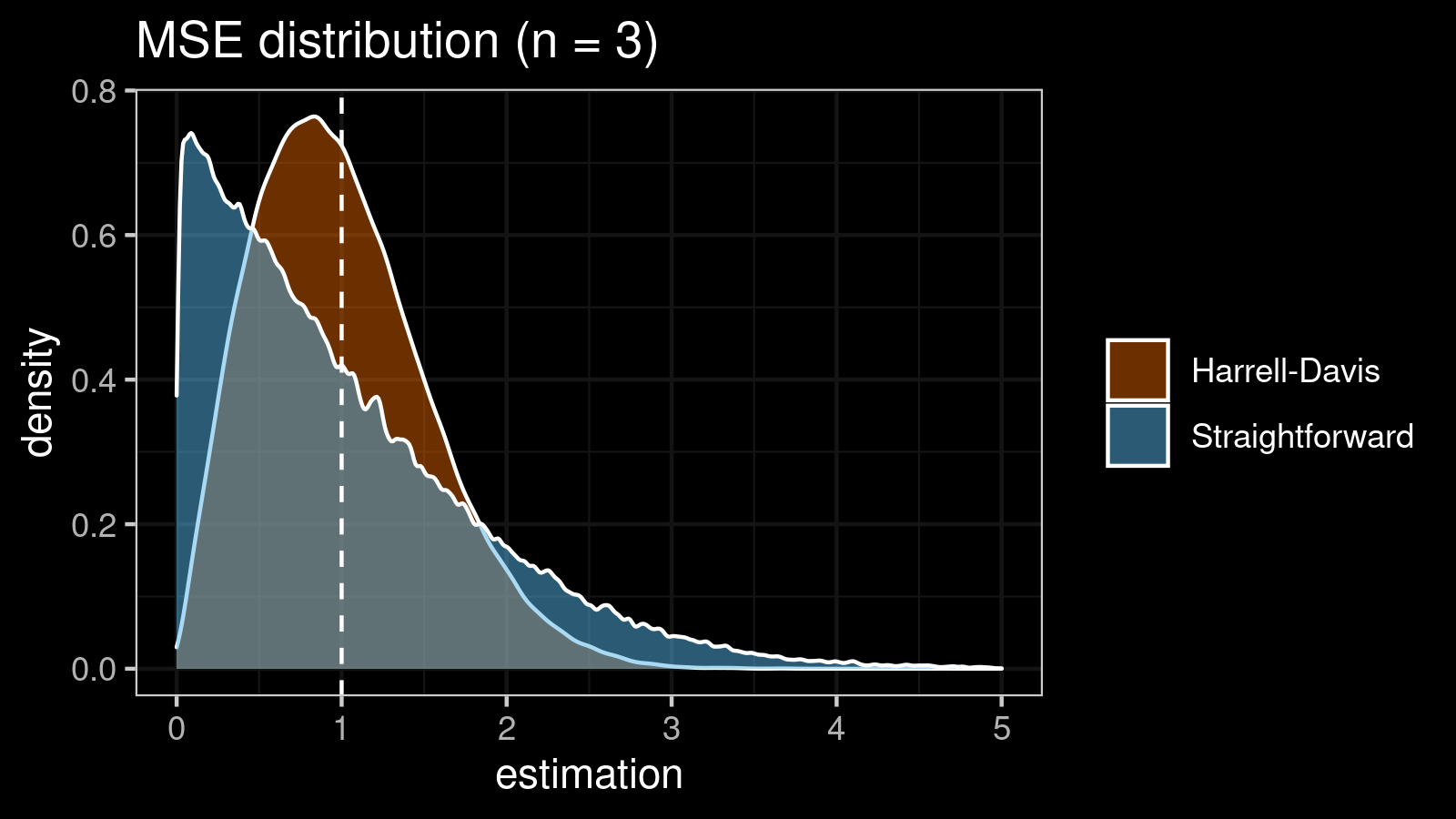

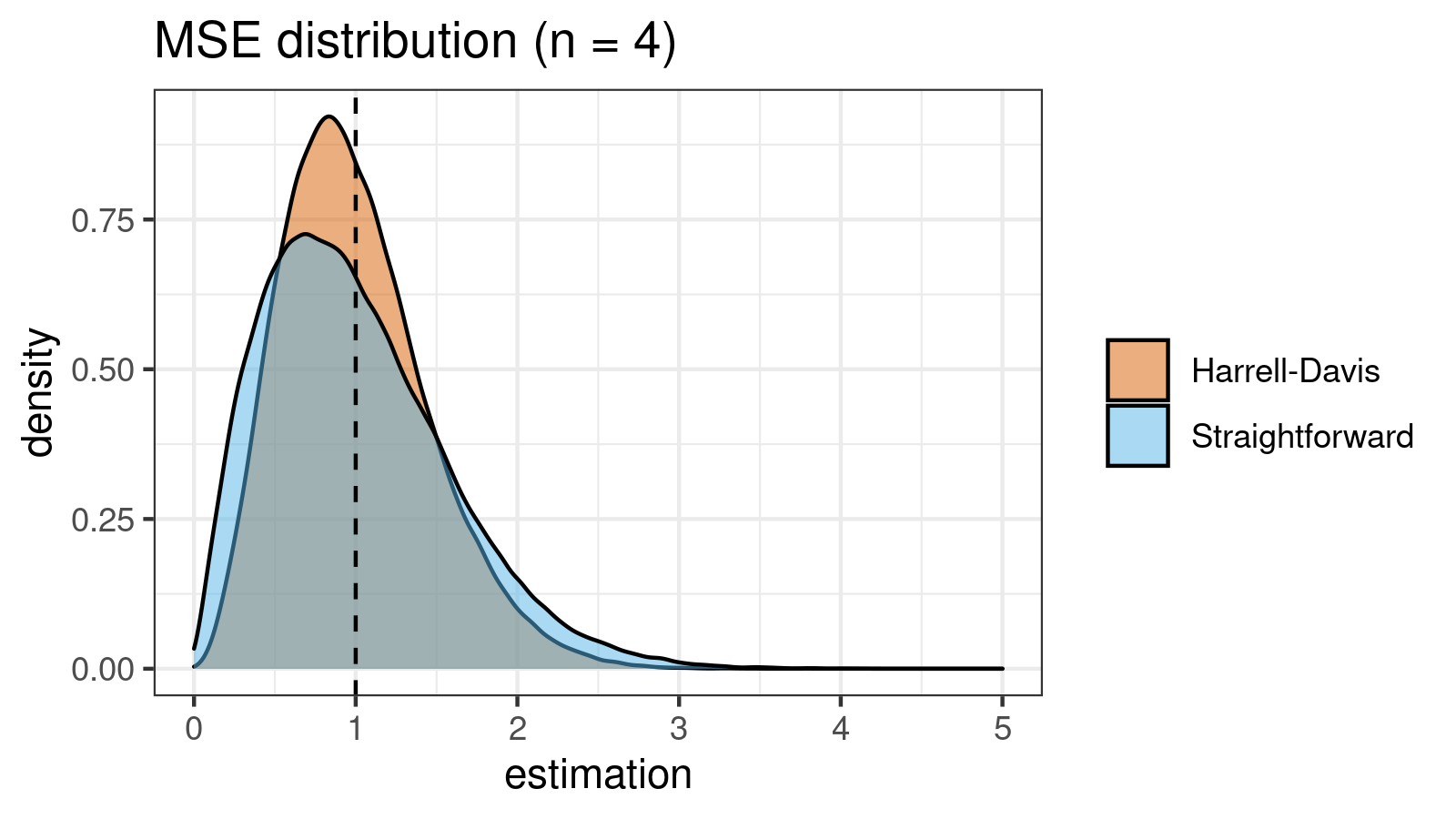

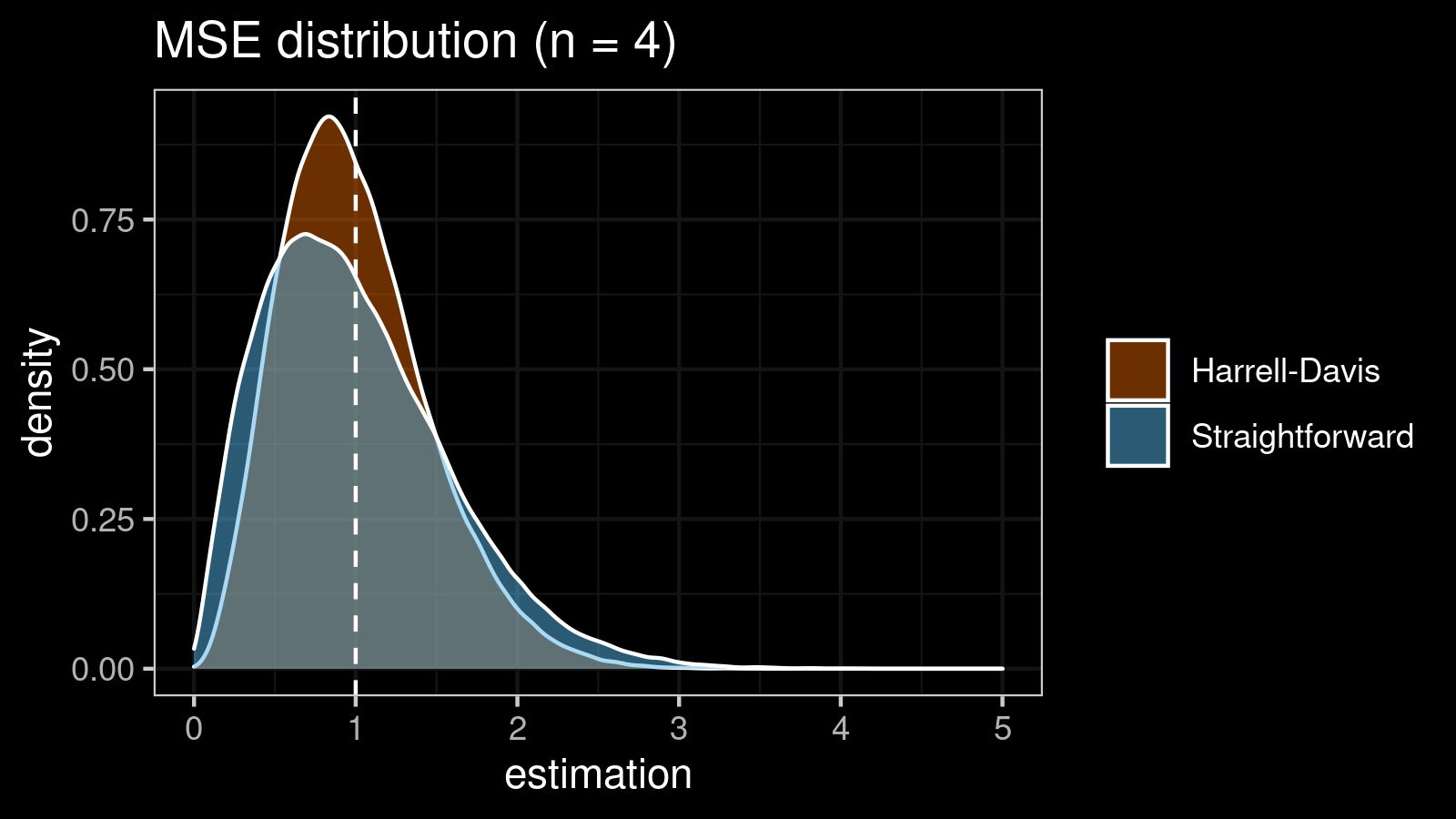

It’s time to compare the straightforward and the Harrell-Davis-based $\textrm{MAD}$ estimators in terms of the mean squared error. To estimate the $\textrm{MSE}$, we also use numerical simulations. Here are the results for some $n$ values:

| n | Straightforward | Harrell-Davis |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.690 | 0.272 |

| 4 | 0.327 | 0.205 |

| 5 | 0.341 | 0.181 |

| 10 | 0.136 | 0.100 |

| 20 | 0.069 | 0.055 |

| 30 | 0.045 | 0.038 |

| 40 | 0.034 | 0.029 |

| 50 | 0.027 | 0.024 |

| 100 | 0.014 | 0.012 |

As we can see, the difference between estimators for small samples is tangible. For example, for $n = 3$, we got $\textrm{MSE} \approx 0.69$ for the straightforward estimator vs. $\textrm{MSE} \approx 0.27$ for the Harrell-Davis-based estimator. Below you can see density plots of $\textrm{MSE}$ for the above $n$ values.

Conclusion

In this post, we discussed the unbiased $\textrm{MAD}_n$ estimator which is based on the Harrell-Davis quantile estimator instead of the straightforward median estimator. The suggested estimator is much more efficient for small samples because it has smaller $\textrm{MSE}$. It allows using $\textrm{MAD}_n$ as a efficient alternative to the standard deviation under the normal distribution with higher accuracy.

References

- [Harrell1982]

Harrell, F.E. and Davis, C.E., 1982. A new distribution-free quantile estimator. Biometrika, 69(3), pp.635-640.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2335999 - [Hayes2014]

Hayes, Kevin. “Finite-sample bias-correction factors for the median absolute deviation.” Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation 43, no. 10 (2014): 2205-2212.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03610918.2012.748913 - [Park2020]

Park, Chanseok, Haewon Kim, and Min Wang. “Investigation of finite-sample properties of robust location and scale estimators.” Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation (2020): 1-27.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03610918.2019.1699114 - [Box1958]

Box, George EP. “A note on the generation of random normal deviates.” Ann. Math. Statist. 29 (1958): 610-611.

https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177706645