Calculating gamma effect size for samples with zero median absolute deviation

In previous posts, I discussed the gamma effect size which is a Cohen’s d-consistent nonparametric and robust measure of the effect size. Also, I discussed various ways to customize this metric and adjust it to different kinds of business requirements. In this post, I want to briefly cover one more corner case that requires special adjustments. We are going to discuss the situation when the median absolute deviation is zero.

Recall

First of all, recall the general equation for the gamma effect size for the $p^\textrm{th}$ quantile:

$$ \gamma_p = \frac{Q_p(y) - Q_p(x)}{\operatorname{PMAD}_{xy}} $$where $Q_p$ is a quantile estimator of the $p^\textrm{th}$ quantile, $\operatorname{PMAD}_{xy}$ is the pooled median absolute deviation:

$$ \operatorname{PMAD}_{xy} = \sqrt{\frac{(n_x - 1) \operatorname{MAD}^2_x + (n_y - 1) \operatorname{MAD}^2_y}{n_x + n_y - 2}}, $$$\operatorname{MAD}_x$ and $\operatorname{MAD}_y$ are the median absolute deviations of $x$ and $y$:

$$ \operatorname{MAD}_x = C_{n_x} \cdot Q_{0.5}(|x_i - Q_{0.5}(x)|), \quad \operatorname{MAD}_y = C_{n_y} \cdot Q_{0.5}(|y_i - Q_{0.5}(y)|), $$$C_{n_x}$ and $C_{n_y}$ are consistency constants that makes $\operatorname{MAD}$ a consistent estimator for the standard deviation estimation.

The problem

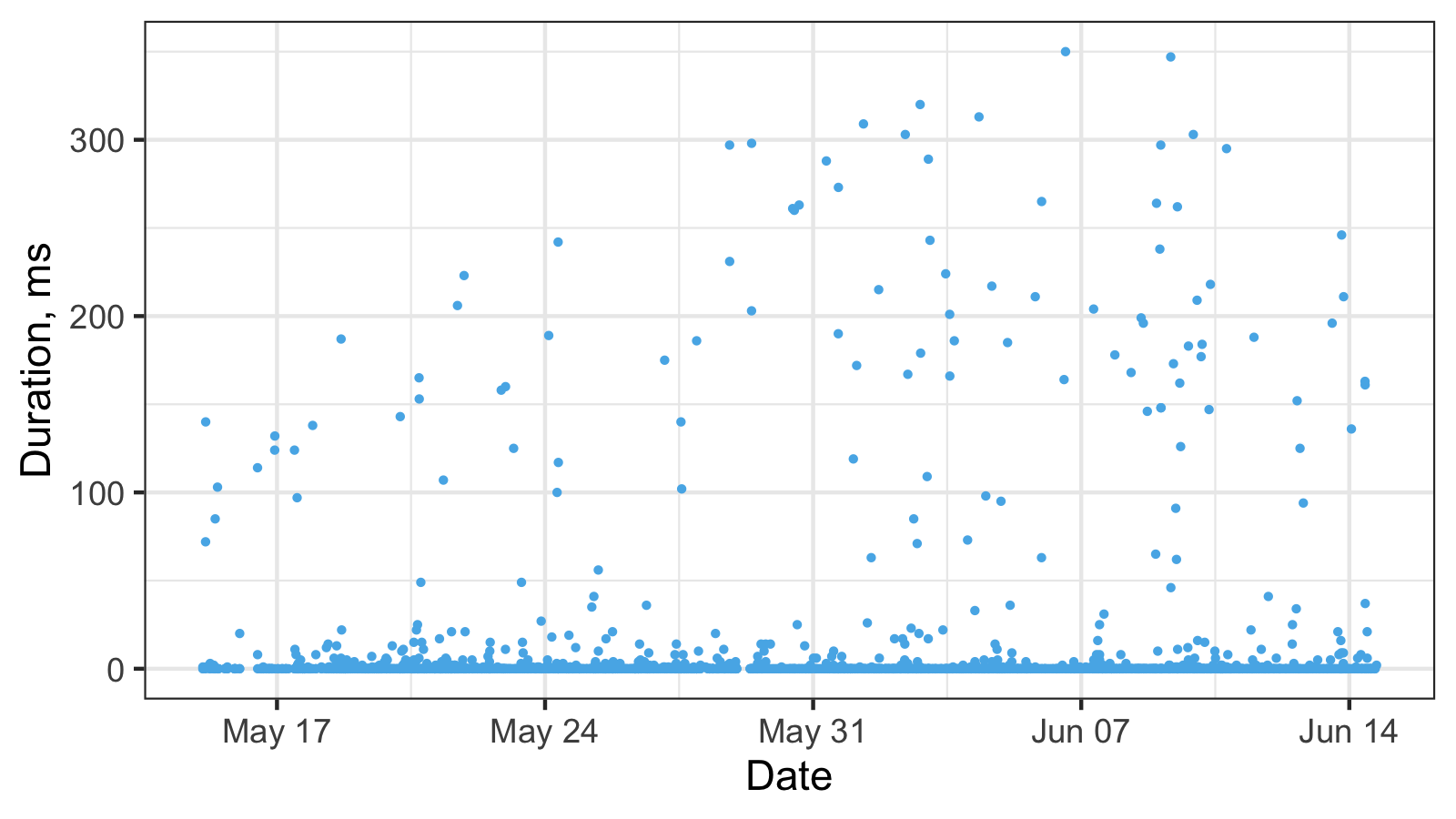

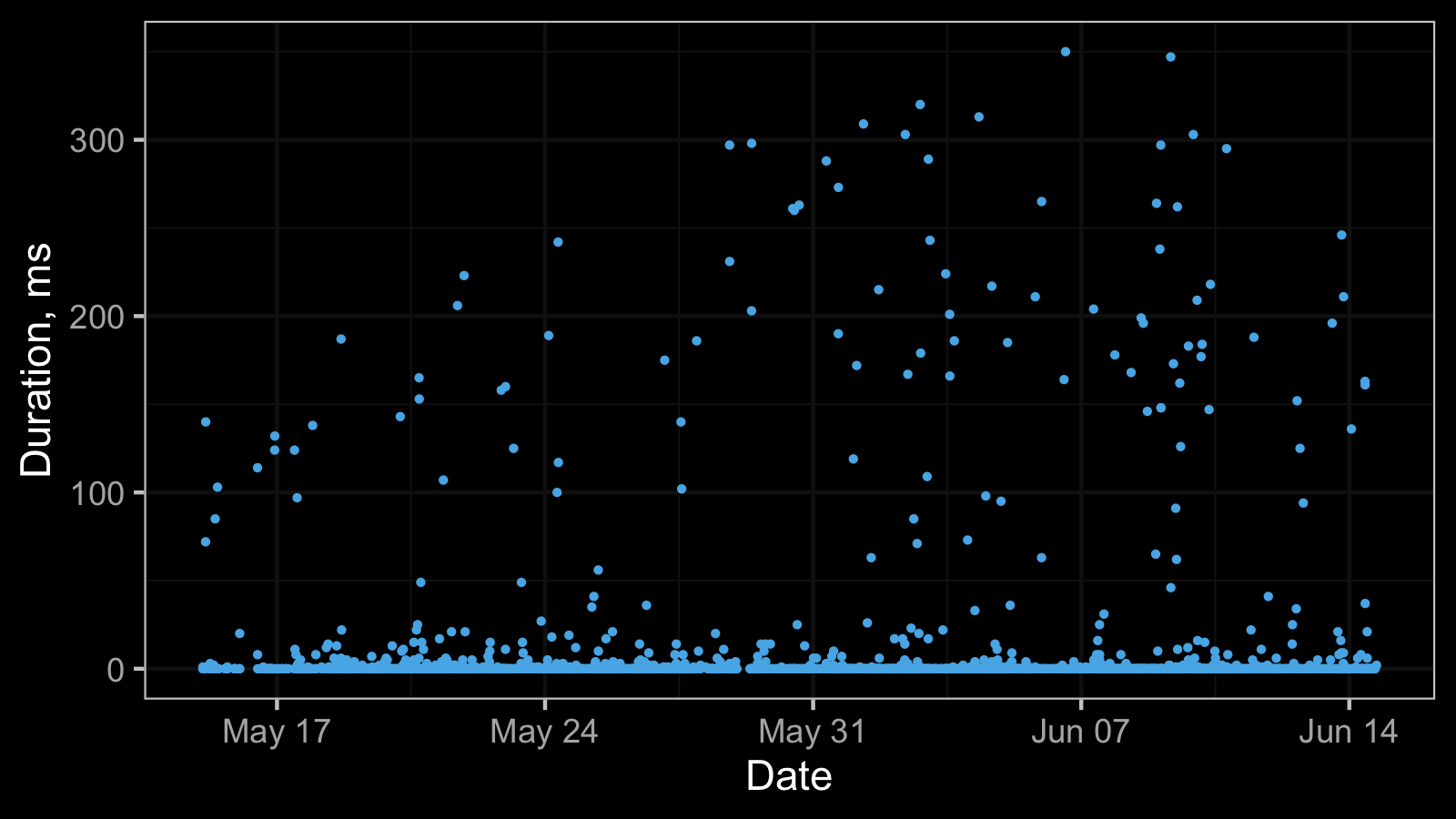

Here is a real-life dataset from my previous post:

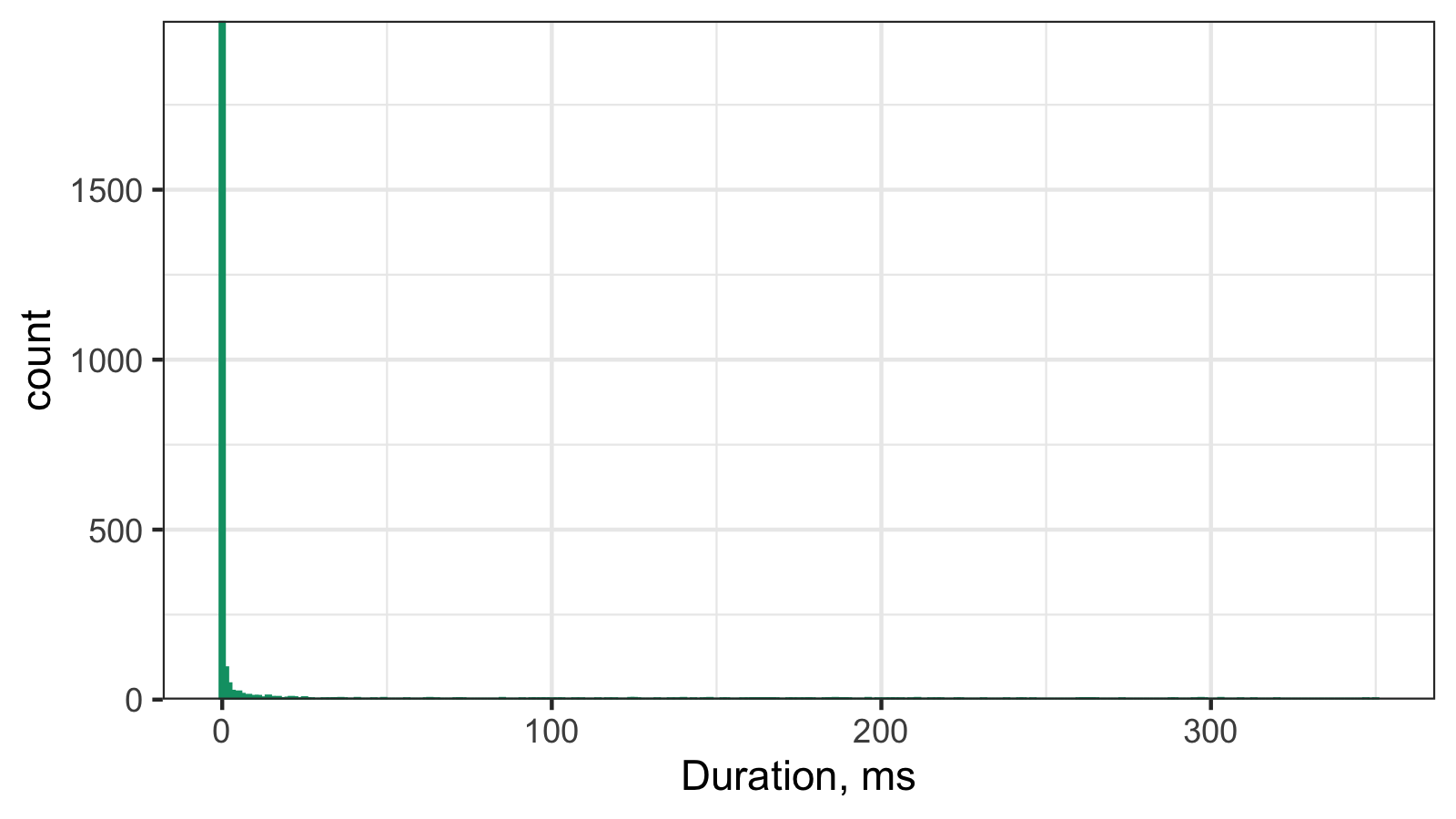

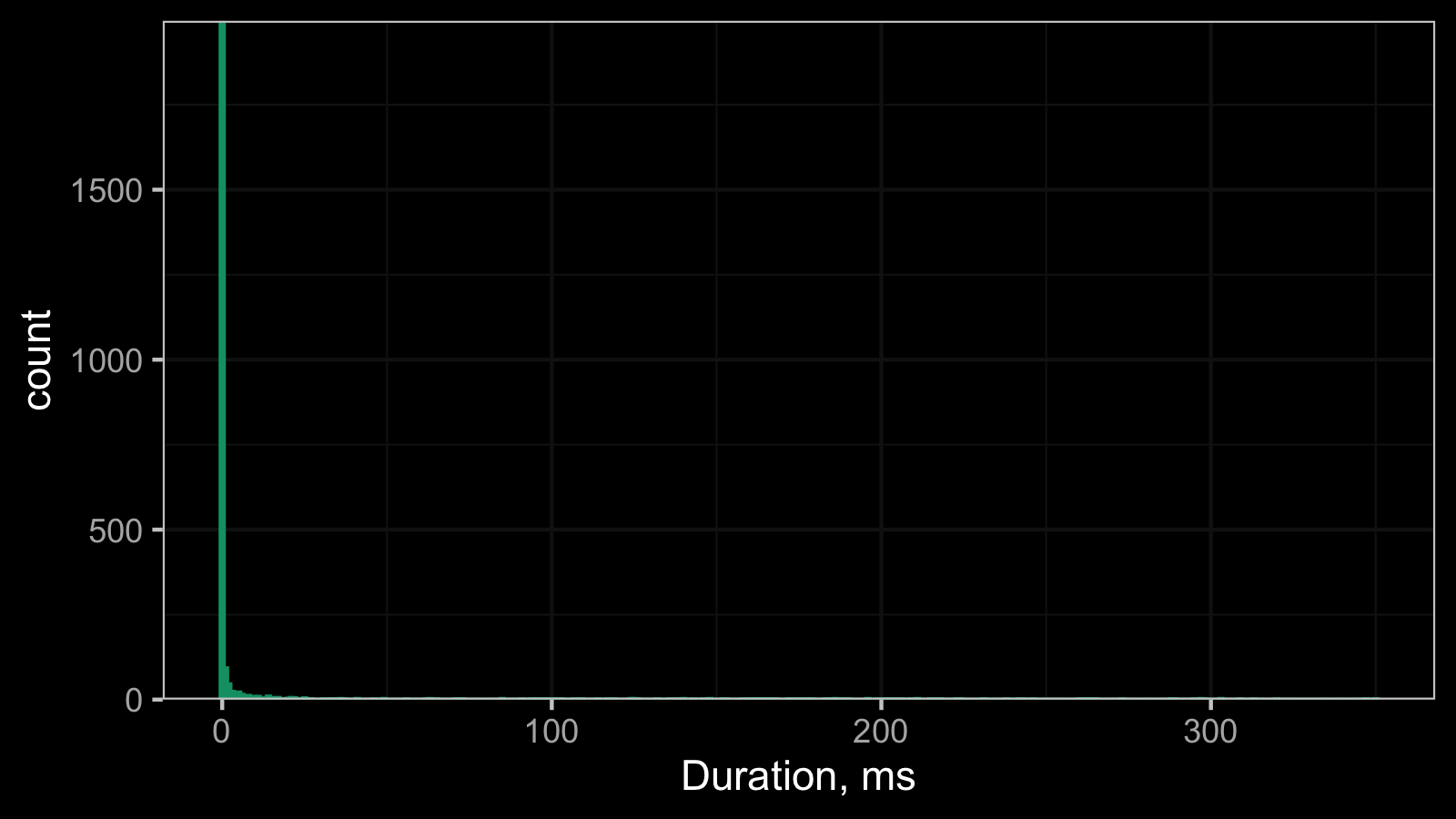

And here is the corresponding histogram:

It’s hard to work with such a histogram because of the scale, so here is its raw data:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

1996 92 45 23 20 21 14 5 11 5 8 8 3 3 9 5

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 26 27 31 33 34 35 36

3 5 1 1 3 5 4 1 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 2

37 41 46 49 56 62 63 65 71 72 73 85 91 94 95 97

1 2 1 2 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1

98 100 102 103 107 109 114 117 119 124 125 126 132 136 138 140

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 2

143 146 147 148 152 153 158 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168

1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

172 173 175 177 178 179 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 196 199

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 2 1

201 203 204 206 209 211 215 217 218 223 224 231 238 242 243 246

1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

260 261 262 263 264 265 273 288 289 295 297 298 303 309 313 320

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 2 1 1 1

347 350

1 1

These numbers mean the follow: we observed 0ms 1996 times, 1ms 92 times, 2ms 45 times, and so on.

And here are the same set of numbers scaled to percents:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

82.68 3.81 1.86 0.95 0.83 0.87 0.58 0.21 0.46 0.21 0.33 0.33 0.12

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 26

0.12 0.37 0.21 0.12 0.21 0.04 0.04 0.12 0.21 0.17 0.04 0.17 0.04

27 31 33 34 35 36 37 41 46 49 56 62 63

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.08

65 71 72 73 85 91 94 95 97 98 100 102 103

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04

107 109 114 117 119 124 125 126 132 136 138 140 143

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04

146 147 148 152 153 158 160 161 162 163 164 165 166

0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04

167 168 172 173 175 177 178 179 183 184 185 186 187

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04

188 189 190 196 199 201 203 204 206 209 211 215 217

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04

218 223 224 231 238 242 243 246 260 261 262 263 264

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04

265 273 288 289 295 297 298 303 309 313 320 347 350

0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04

Thus, we observed 0ms in the 92.69% cases, 1ms in the 3.81% cases, 2ms in 1.86% cases, and so on.

In this data set, both the median and the median absolute deviations are zero.

Here the observed data could be perfectly described using the

discrete Weibull distribution.

If we try to compare samples from similar distributions using the gamma effect size, we get a problem because of the zero denominator.

QAD to the rescue

In the above scenario, it’s meaningless to compare medians values. We can have a situation of different distributions with equal median values (and zero median absolute deviations). In such cases, it makes sense to compare higher quantiles instead of the median. However, it doesn’t solve the zero denominator problem.

The problem can be solved using the Quantile Absolute Deviation(QAD) around the given quantile:

$$ \operatorname{QAD}_x(p, q) = C_n \cdot Q_q(|x_i - Q_p(x)|) $$It’s easy to see that the $\operatorname{MAD}$ is just a special case of $\operatorname{QAD}$:

$$ \operatorname{MAD}_x = \operatorname{QAD}_x(0.5, 0.5). $$By analogy with $\operatorname{MAD}$, we can define the pooled quantile absolute deviation $\operatorname{PQAD}_{xy}$:

$$ \operatorname{PQAD}_{xy}(p, q) = \sqrt{\frac{ (n_x - 1) \operatorname{QAD}^2_x(p, q) + (n_y - 1) \operatorname{QAD}^2_y(p, q)}{n_x + n_y - 2}}, $$When we estimate the gamma effect size of the $p^\textrm{th}$ quantile $\gamma_p$, it makes perfect sense to evaluate the quantile absolute deviation around the same quantile. Although I don’t have specific recommendations for the value of $q$, we can start with $q=0.5$ as a starting point and adjust it if necessary.

Conclusion

We should always remember that real-life data contains tons of corner cases that may become a problem if we want to analyze this data. It’s better to think about these corner cases in advance and come up with proper solutions. In this post, we patched the gamma effect size for distribution with zero median absolute deviation using the quantile absolute deviation. This trick allows comparing higher quantiles for such distributions. A typical real-life example is the Weibull distribution.